BEIGE BEIJING

绿色边界

绿色先锋

中国的煤炭,正如中国政府在他们的21项议程中所叙述的一样,可以在现有的环境条件下以更为环保的方式被开发。这一目标已正式形成。尽管和其它的国家可持续发展的计划很像,这个计划同样可以反映现阶段中国对西方现代化的态度,对自然与社会之间的传统文化观念。意识形态和政治

力量在不远的将来会塑造世界的生态环境。而中国环境的未来,将主要依赖于这个国家和人民想要什么样的将来,以及为可持续发展作出牺牲的认可。

The GREEN EDGE*

Text: Erich W. Schienke,PHD, and Neville Mars

The Wall of Questions Standing in front of Beijing’s Greener Future

What do citizens want a city like Beijing to be? What functions should the city best serve — at what costs, and for what trade-offs? How do present land-use choices affect future conditions? Do higher densities raise or lower the overall ecological footprint? What is reasonable consumption for an urban dweller, and how do you increase the efficiency of their residential blocks? Is there hope for a green urban landscape in China? Can the necessary institutional shifts be put in place to support urban greening beyond the superficial?

“Beijingers enjoy breathing fresh air for almost two out of every three days”

– Chinese state media

A thick haze of pollution lingers over Jing Hu*. Large pools of cool air settle near the surface, heavy with emissions from factories, power

plants, automobiles, and millions of domestic stoves. The widespread burning of low grade coal, and the use of dirty petrol derived from

cheap sour crude, further exaccerbates the smog problem. Dust clouds swept down from the desertifying north regularly enter into

the mix. Heavy pollutant concentrations cause passing clouds to hang onto their moisture, leading to conditions of low visibility–low

precipitation. It is estimated that 75% of China’s city dwellers live below the country’s acceptable air-quality standard.

Imagining Beijing’s Ecological Future

China’s goal, as articulated by the Central Government in their Agenda 21 1 plans, is to be able live in a way that is more ecologically sound than that exhibited by the current environmental conditions and human impacts. This objective, now formalized, arises out of a variety of complex interactions between the State, provincial and local constituents, and international governance regimes such as the UNDP and UNEP. Though similar to other national plans for sustainable development, it also reflects developments that extend from China’s currently shifting attitudes towards Western modernization, and its (often conflicting) historical/traditional cultural attitudes towards the relationship between nature and society. 2 While it is difficult to predict the outcome, this mélange of ideological and political forces will present as real world ecological consequences in the near future. How choices will be made about China’s environmental future relies mainly on the kind of future it imagines for the nation, its people, and their environment, including a recognition of the sacrifices that will undoubtedly be needed to achieve sustainability.

The concept of an “imaginary” has been developed in anthropology and political ecology as a means to describe the body of ideological, ethical, and rhetorical forces that scientists, planners, decision-makers, and citizen activists (together referred to as “environmental subjects”) must engage with to accomplish in their goals. Imaginaries are higher-order discursive systems that allow local environmental subjects to work through double-bind situations, such as creatively turning a “no-win” situation, presented by greening versus development (traditionally a paradox), into a “win-win” situation. Basically, environmental imaginaries provide environmental subjects with ways of expressing problems and solutions in new terms, concepts, metaphors, and symbols. That is, locally situated environmental subjects are “tapping into” systems that are sustained at a higher-order of magnitude or on a larger-scale than might be apparent if reading only the local context: a mode of thinking particularly important to sustainability.

Environmental imaginaries become a way to tap into new ways of understanding the world, and the invention of new modes to interpret what Kim Fortun calls the ‘languages for which there are no indigenous idioms.’ New environmental situations and political complexities beget new concepts that force the articulation of new terms. The concept of an environmental imaginary works to describe how environmentally charged concepts — such as a Green Olympics in Beijing, or xiao kang* (a well-off society) — are conceptualized in the context of broader Chinese interests regarding the co-construction of society and nature, or what Ma Shijun and Wang Rusong call the Social Economic Natural Complex Ecosystem (SENCE).

Two instantiations of environmental imaginaries are currently in rapid and potent circulation throughout the Beijing development mindset, namely the Green Olympics in the shorter term (to 2010), and the “Green-city” or “Eco-city” in the longer term (to 2020 to 2100).

Sustainability

可持续发展(ke chixu fazhan) are the Chinese characters for “sustainable development”. Breaking the term down to its constituent parts, 可(ke) means “able”, 持续 (chixu) means “continuous”, and 发展 (fazhan) means “development”. So, the term for sustainable development in Chinese implies the ability to develop continuously. Parsed out and taken up uncritically, this phrasing stands in contrast to how the term was originally used in the Brundtland Report, which defines sustainable development as development which ‘meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland 1987). In evaluating the status and dynamics of various elements of China’s ecosystem and ecosystem services, the Central Government is currently very much concerned with its ability to develop continuously, perhaps more so than it is with the long-term ability to meet the needs of its vast population. The perceived threat to the Central Government seems to be that if economic development is not sustained then political unrest and instability are sure to follow. Successful approaches to sustainable development would need to secure both short-term gains in economic development, while at the same time investing in the long-term security of ecological resources and services.

Olympic hurdles 1

For the city of Beijing, the driving force behind current infrastructural, economic, cultural, and environmental developments is, without a doubt, the 2008 XXIX Olympic Games. These Olympics are being promoted as a Green Olympics, which aim to align themselves with the principles of green energy, recycling, and sustainable development. This aspect of the Beijing Olympics has proved to be fertile ground for increasing public awareness of “going green” in China, and has become a touchstone for integrating eco-city thinking into the mindset of Beijing’s urban planners. Going green, of course, can be widely interpreted. Holding the Olympics in Beijing signifies the first time an Olympic Games is being held in a developing country since the 1968 Mexico City Olympiad. Holding a “green games” in China represents a different level of investment in capacity building than for countries such as Australia, the US, or the UK. Thus, the expected greening result for Beijing is at a relatively higher bar than it would be for developed countries. This push in capacity is driving the call for an increase in eco-environmental scientific analyses, and is putting intense attention on “greening” new development throughout the city.

Green Olympics

‘Unlike the Sydney Olympic Games, Beijing’s Green Olympics will be an ecological event characterized by an age of globalization and information. It will need the support of harmonious ecological services, environmentally sound high-tech, and the long cultural tradition of “man and nature be in one”. To combine the old tradition with the new transition to realize “New Beijing, Great Olympics”, a new integrative concept of eco-Olympics has been developed which consists of green Olympics, scientific-technological Olympics and cultural Olympics, based on the principles of physical, economic and cultural ecology respectively.’ 5

Wang, R. S. ‘The Eco-Origins, Actions and Demonstration Roles of Beijing Green Olympic Games’ Journal of Environmental Sciences (October 2001)

“Eco” here means a driving force, an action, a culture, a kind of vitality and an adaptive process leading to sustainable development. It is a kind of social behavior which pushes forward development while conserving the environment, and it is also a mechanism embodying the Olympic spirit of competition, symbiosis and self-reliance. It means internal harmony between structure and function, and systematic health in dynamics and cybernetics.

The Green Olympic spirit needs not only morphological green (blue sky, green land and clean water), but also functional green (eco-services, eco-institution and eco-consciousness). Furthermore, it seeks a dynamic green that brings man’s potential to its full play according to ecological principles. To achieve this, it is necessary to green not only the landscape, but also the process of production and consumption as well as people’s minds and behavior, which means a further sublimation of the Olympic spirit.

However, China’s expression to the world of its “eco-spirit” does not end with the 2008 Olympics. In 2010, Shanghai will host the World Expo, which is going to be another large scale “green city” and “eco-friendly” urban development project. (“Eco-tourism” is also another very popular and contested instantiation of an environmental imaginary within the development of Chinese nature reserves.) While there has been much discussion of corporate “green-washing”, the “green-washing” of state-run endeavors appears to be an area which the central government is taking on fully. The extent to which China, and Beijing specifically, is capable of achieving the goals for a Green Olympics and beyond, will, in the global arena, determine how much of “going green” is a shift in political rhetoric versus a shift in fundamental goals and capacity building in the eco-environmental domain. It needs to be acknowledged, however, that this shift in rhetoric does not come without sincere and focused pressures from scientists and the public to pay closer attention to the costs of environmental damage.

Green performance in a Green Olympics may indicate how much of China’s “going green” is a shift in political rhetoric versus a shift in fundamental goals.

绿色表演在一个绿色的奥运会中,可以显示出中国的“进行中的绿色”有多少是政治言辞有多少是在向基本目标迈进。

Green-city to Eco-city 6

The concept of the successful Chinese city has changed over the past 25 years from a centrally planned center of commodity production to a market-driven center of commercial production. The transition over the past decade from a planned economy to a socialist market economy (with “Chinese characteristics”) is the primary driver for this switch. With it comes a de-emphasis on producing commodities to meet state objectives, and a greater emphasis on allowing the market to determine the efficiency and types of production in urban centers, thus allowing certain regions in China to specialize rather than generalize their industry. Such an expected and observed growth in production specialization yields two significant results: first, specialization brings with it industrial modernization, which (arguably) eventually leads to ecological modernization; and second, inefficient and heavily polluting facilities are closed down because they are not competitive within the market nor are they viable producers for the market. For example, the ISO 14000 family of environmentally focused management standards is becoming globally popular, and if a Chinese company wants to supply to another, usually offshore, company which already complies with these standards, then the Chinese firm will very likely also need become ISO 14000 certified.

In step with other trends in municipal funding and other favors shown to Beijing compared to other municipalities throughout the country, the capital region rarely undergoes mandatory blackouts/power-shutdowns. In an effort to reduce air pollution, major power producing plants have been moved beyond the current limits of the more urbanized areas in and around Beijing. And as a further effort to address energy shortages and pollution problems, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) has passed a national Law on Renewable Sources in March 2005. This renewables law, a remarkably progressive law for a developing country, has set the goal for 10% of all energy consumed in China to be derived from renewable sources by 2010. 7

Energy

China’s energy sector is tremendous, and growing. In 2001 China consumed 9.8% of the world’s total energy output, and by 2025, it is projected to account for 14.2% of the world total (US DOE 2006). As Article 3 of Electric Power Law of the People’s Republic of China the states, ‘the electric power industry should meet the needs of the development of the national economy and the society and should therefore develop slightly ahead of the other sectors of the economy. The State encourages and provides guidance to lawful investment in the development of power resources and establishment of power-generating enterprises by economic organizations or individuals at home and abroad.’ It is no wonder that most of the funding from the US, the UN, and the World Bank has gone into China’s energy sector: energy capacity drives the rest of the country.

But Beijing’s long-term pressure to “go green”, beyond the 2008 Olympics and the 2010 renewables target, stems from more pressing realities such as severe water shortages, air pollution, land-use density, urban heat island effects, growing automobile ownership and traffic, and the congregation of inefficient industrial facilities. Addressing these issues requires a great deal more time for the market economy to focus fully, for rule of law to be firmly established, and for better coordination of efforts across planning departments. These are all met with problems of corruption, inherent loopholes and legal paradoxes, vague policies, bad loans, lower technical capacity, outdated facilities, top-heavy bureaucracy, and the ubiquity of inefficient communication and data sharing.

The GREEN EDGE*

The two environmental imaginaries, the Green Olympics and eco-city Beijing, produce very real results, particularly in motivating planners and politicians towards thinking more broadly and deeply about sustainability, green designs, public transportation, and energy efficiency. The current trend in urban development around Beijing, however green it may be marketed as, still has a long way to go before reasonable claims of sustainability can be met. For such shifts in development to occur would require not just a few key politicians to think green or have goals in accordance with sustainable concepts; rather, it implies a shift in the entire culture itself away from the direction it is currently heading — i.e. that of heavy consumption of disposable material goods and neo-liberal emphases on the success of the individual.

There are no sincerely robust examples of urban-scale sustainability we can point to in any major urban region of the world, so we are not entirely sure what success looks like in these regards. However, in the absence examples, environmental imaginaries provide us with conceptual frameworks and sets of goals that, hopefully, point us in the direction of what sustainable success might be.

There are no sincerely robust examples of urban-scale sustainability we can point to in any major urban region in the world.

世界上没有哪个大都市堪称是可持续发展城市的典范。

Water

Water quality and quantity is a significant factor for cities like Beijing and Shanghai, and becomes a major problem in small towns and villages with heavily polluting industries such as electroplating, MSG manufacturing, and smelting. Not far out of town the heavy use of fertilizers causes excessive run-off into local streams and lakes, where high levels of nitrogen and phosphates causes rapid eutrophication and die-off of fish and other aquatic wildlife due to low levels of oxygen.

The water table in Beijing has reportedly fallen by approximately 50-60 meters since the beginning of major industrial development and expansion around the city. This is unsurprising considering that Beijing is a city with about one fifth of the global average of fresh water supply per capita. A large northwest canal to the Yellow River is under construction; however, while the Yellow River rages massively raging in its more western reaches, it is dried up for more than half the year before it reaches the Bohai sea. Water-use efficiency is particularly low in China.

‘Due to unnecessarily huge irrigation quotas, water is wasted on a large scale. It is estimated that water use efficiency (WUE) is only 0.4. The WUE of channels in most irrigation areas is 0.4-0.6. In Northern China, agricultural irrigation seriously wastes water, with a WUE of 0.4-0.5 in most channels, and the WUE in the catchment of the Haihe River is 0.45. In Northwestern arid regions, the irrigation quota is 16,537m3/hm2, 1.4 times greater than the average irrigation quota. In Ningxia, the irrigation quota is 32,550m3/hm2, 2.8 times greater than average. In northern China, the irrigation quota is 7,500–12,000m3/hm2, or 2-5 times greater than crop water requirement. Water wasted by agriculture is believed to exceed 10x1010m3 every year.’ 10

By 2050, the projected water use for Beijing far outweighs current capacity. A much stricter system for charging for water consumption will help to curb waste; this entails better monitoring of use, and higher pricing of water per unit consumed. A much higher efficiency of water usage needs to occur in the irrigation system. For example, ‘even in the water short North China Plain, farmers produce on average only about 0.85kg of grain per m3 of irrigation water, compared to over 2kg in the US.’ 11

Space

Outside of population growth itself, there are two primary factors eating up space in Beijing: the most notorious is the private automobile, followed by the expansion of floor space in new developments. As Huang points out, the ‘overall level of housing consumption in Beijing has increased significantly over time, from less than 4m2 of living areas per capita in the 1950s to 11.64m2 in 2001.’ (Huang 2005) 12

The growth rate of automobile ownership in Beijing is also tremendous. At the current rate (2006), there are approximately 200,000 new cars on the Beijing roads every year, bringing the 2006 total to approximately 1.3 million private cars. According to statistics from the Beijing Traffic Management Bureau, there are approximately 1,000 new vehicles — including cars (~64%), trucks, motorcycles, scooters, etc. — licensed every day for the roads of Beijing. This does not count the extra licenses given out by surrounding Hebei province, which can be used anywhere outside of the 4th ring road. Simply making room for parking the cars is becoming one of the greatest developmental pressures on preserving green space throughout Beijing. Approximate calculations suggest that the surface area required to park the current car fleet of Beijing is approximately 26km2 (at 20m2/space). Setting aside multi-story car parks, this represents 3.8% of the entire surface area of Beijing within the 5th ring road. Based on a 2002 study by Tsinghua University, if car-buying trends in Beijing match the rest of the country, the car population could top 7 million by 2020. 7 million parked cars would cover about 21% of the surface area within the 5th ring road.

The seriousness of this problem is compounded by the falling popularity of the bicycle. Once the great icon of Beijing transportation, increasingly the bicycle is being associated with backwardness and economic disadvantage. The implications of an emergent middle class moving from bicycles to cars go beyond oil consumption to urban space consumption: a bicycle is estimated to require 2m2 per unit, as opposed to the car’s 20m2.

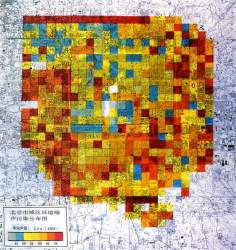

The urban heat island effect (UHI) 13 is another significant factor concerning the density of built up areas throughout the city. UHI effects can impact the micro-climate of a city significantly, generating a difference of 10˚C or more from surround areas, and greatly increasing the demand for energy intensive air-conditioning in the hotter months. Various studies conducted by Xiao Rongbo demonstrate the correlation between Beijing’s high density of impervious surfaces and tall buildings and an increase in the occurrence of UHIs. This is an issue which can be planned for in the future, particularly by considering how to lessen non-porous surfaces.

Building

China’s leaders appreciate the magnitude the Chinese urban landscape has in the ecological equation. The green objectives aimed at cities as formulated by the Ministry of Construction are impressive to the point of almost unbelievable. By the end of 2010, all Chinese cities are expected to reduce their buildings’ energy use by 50%; by 2020, that figure should be 65%. Furthermore, by 2010, 25% of existing residential and public buildings in the country’s large cities should be retrofitted to become greener; 15% in medium-sized, 10% in small cities. Over 80 million m2 of building space should be powered by renewable energies. In China such astounding goals are not necessarily utopian. Still it is unlikely that in 2020 this much of China’s new urban residences will include serious sustainable measures when in 2005 it was less than 3%. The impact of China’s cities on the environment is hard to overestimate. Of the 15 billion m2 floor space in China only 1.5 billion are in cities, 14 yet here the real progress can be made. China’s increase in oil consumption until 2015 will be almost entirely for road transport; oil consumption for transportation alone is likely to increase from 0.8 to 3.5 million barrels a day. 15As much as 28% of China’s current energy consumption can be attributed to residential use (expected to double by 2020). Include commercial use and the inert and grey energy stored in the buildings’ material and this adds up to over 40%.

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, its successful bid for the 2008 Olympic Games, and the country’s general integration into the world economy have all contributed to an absolute urban investment boom. The World Bank estimates that between now and 2015 roughly half of the world’s new building construction will take place in China. China’s Ministry of Construction estimates it will double its current building stock by 2020, predominantly for housing. This means 30 billion m2 will need to be constructed over the next 15 years. This is equivalent to the entire building mass of a 25 country large European Union. The building industry alone accounts for approximately one-third of China’s electric power use, and the process of demolition and building delivers 35% of the total green house gas emissions and a host of indirect environmental problems. The total sum of all these figures is hard to establish but is likely to be the dominant factor in China’s energy and environmental equation. What should be emphasized is that China’s planning, construction and design are inextricably linked with its future energy needs. These industries will have a detrimental impact on the environment if they won’t or can’t adopt a sustainable strategy before this construction wave has been completed.

Food/Waste

Agricultural production has an extreme effect on overall water quality and quantity, though it is slowly being surpassed by industrial usage. 16 However, agricultural consumption also plays a significant role in contributing to the release of greenhouse gasses, namely CO2 and methane. Food scraps are the largest component of municipal solid wastes (MSW), and are the richest in carbon release (during decomposition) amongst the MSW. Various studies have demonstrated that carbon output per capita increases as per capita GDP of a city increases. 17 This is, in part, due to a richer diet, in particular an increase in the consumption of meat and rice. 18 An increase in transportation is also implicit in wider distribution of food, particularly since you no longer need to have a residence card, or hukou*, in a city to buy food there.

What is certain is that further experimentation is needed, both in enhancing education of the public about sustainability, and particularly in coming up with new designs for green living without erasing the valuable characteristics and traditions of living within a community setting. It is in this context that we introduce the concept of the green edge*, a term that not only refers to the perimeter of the urban development, but also aspires to describe the very boundaries of conceiving sustainability and of living green. Perhaps the best way to understand the green edge* extends from landscape ecology, which has identified that boundaries in managed ecosystems, such as the border of a large wooded area in a park, need to be made complex and not linear. A complex boundary between vegetation types, it was discovered, provided better conditions for biodiversity. Such lessons should inform how green space is planned in areas undergoing new development as a technique for combating sprawl and integrating complex boundaries between human ecosystems.

Appropriate designs: Gao Bei Dian (GBD) and Hybrid Hutongs*

Urbanization is the single largest agglomeration of influences on China’s environment. Urban effects are found across all sectors of the economy, span multiple spatial and social scales, and influence even the far reaches of natural ecosystems in remote “under-developed” regions. The rise of the urban middle class in China is driving the desire for newer more luxurious building stock, for private vehicles, for increased consumer-orientated production, and for eco-tourism, which is transforming sleepy little towns into thriving magnets for urbanites thirsty for a bit of pristine nature. These forces are all major obstacles to the realization of China’s green imaginaries.

Consumption

‘China should not develop in the same way as the US, with high consumption of resources and high emission levels. Otherwise, China will not be tolerated by the world, or even by itself.’

President Hu Jintao

As the world’s largest consumer the threat China poses is all but local. Spearheading the trend of low-cost production and intensive global competition, China’s success or failure to convert to a green economy will determine if new sustainable growth models can be realized across the board.

‘If this doesn’t work for China, it will not work for India or the three billion other people in developing countries who are also dreaming the American dream’

Lester Brown, Earth Policy Institute.

Greening existing built-up areas is very difficult without deep investments in infrastructure or innovative approaches, such as vertical greening. This will likely come over the longer term, but near term payoffs are far more achievable and effective when looking at the greening of areas currently undergoing development.

The two proposals here, GBD and the Hybrid Hutong*, attempt to address many of the problems as well as opportunities that are presented by the green edge*, i.e. thinking at the current plausible limit of urban greening.

The L-Building, which draws its inspiration from the traditional and highly successful Beijing hutong*, introduces the concerns of the individual to planning approaches which often, given the inevitable granularity of big building projects, forget the relevance of issues like community. This mode of thinking is then integrated into a larger scale development, the GBD proposal for an area of East Beijing near the fifth ring-road, which attempts to bring a degree of coherence to the city by considering future transportation routes, the availability of public services, and the recirculation of waste. By imagining greening on levels that are relevant to both consumer satisfaction and consumer greening, and city wide operational efficiency and city greening, the green edge is given a concrete form.

Conclusion: Enhancing Community Capacity towards a Sustainable Future

Successes towards sustainability will begin by asking in all sincerity, ‘what kind of collective life do the Chinese people imagine for themselves, and for others in the world?’ Implied in this are considerations about how much people are willing to risk, sacrifice, adapt, and innovate. How well the Chinese government is able to come out on the positive side of the question will most likely depend upon how equitably such sacrifices are distributed across China’s classes.

Addressing that means facing the double-bind that promises of neo-liberalism’s emphasis on individualism encounters when faced with serious consequences for the environmental commons. While China’s one-child policy was a policy in favor of protecting “the commons”, it has paradoxically hastened the rise of what has to be one of the most individualistic generations China has ever seen. That’s not to say that individual success and wealth should be shunned, but rather, what such success means at an individual level needs to be profoundly reconsidered in the context of sustainability.

Thinking in sustainable terms means accounting for the debts that need to be paid forward — ecological debts that are accrued every time a new housing development is established or new road is put down. However, this is not a cause without support, as sustainable terms are being translated into economic terms, such as with the use of ecosystem services, so they can be included in wider political-economic valuations. Comprehending what this means to an individual’s lifestyle choices, however, will require re-training individuals in how they go about their daily business. Individual happiness and wealth needs to be accounted for, but such happiness is tied into the well-being of the community as well.

As Bryan Norton lays out in his work on sustainability, aligning community goals with environmental values becomes a driving condition for making effective sustainable choices. Establishing these values would include, as Norton argues, taking responsibility for future consequences, making a commitment to ‘future-oriented living’, evaluating how ‘citizens value parts of their environment at a given time’ by ‘focusing on everyday communication’, and developing an empirical foundation to help communities ‘posit a basis against which to judge public processes of adaptive management as they emerge and develop in real situations.’ 19 If we want to put an investment into sustainable development that will affect both the goals of urban level sustainability and individual level consumption patterns, it would be best done at a community level, and focused on communications which increase the awareness of environmental values and practices through greener designs for residential blocks.

Dwelling designs that support both environmental values and community participation will not only provide the conditions for moving towards a more sustainable urban/rurban lifestyle, but will also provide the foundations for a stronger civil society. It is these goals that are infused in the Gao Bei Dian and L-building designs for Beijing. The GREEN EDGE* is the urgent context in which these building experiments need to be refined into successfully reproducible examples of sustainable design for the continually expanding boundaries of China’s cities.

Note

1. ‘Agenda 21 is a comprehensive plan of action to be taken globally, nationally and locally by organizations of the United Nations System, Governments, and Major Groups in every area in which human impacts on the environment.’ http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/index.htm

2. The dichotomy between nature and society is itself more of a Western conceptual framework than a Chinese one, and so making such a comparison already presents problems.

3. Fortun, K. & Fortun, M. ‘Scientific Imaginaries and Ethical Plateaus in Contemporary U.S. Toxicology’ American Anthropologist (107, no. 1, 2004) pp. 43-54.

4. The title of this subsection refers to Liu Xiang, winner of the men’s 110m hurdles in the 2004 Olympic Games. He has become a nationalist symbol for China’s Olympic success.

5. Wang, R. S. ‘The Eco-Origins, Actions and Demonstration Roles of Beijing Green Olympic Games.’ Journal of Environmental Sciences (October 2001)

6. Among urban ecological planners working on Beijing’s Urban Master Plan 2020, a “green-city” is one that appropriately takes into account green space and green planning, including transportation, building materials, urban heat islands, etc. The term “eco-city” is used to express a conception of a far more ecologically-minded city — one that is in a sustainable relationship to all ecosystem services that support it. Most ecological planners I spoke to were of the opinion that while Beijing could become a “green-city” by 2030, it could not reasonably be expected to achieve “eco-city” status much before 2100.

7. According to the US DOE, this is also deemed to be an exceptionally important effort because China’s own oil reserves are only about 10% of the world’s average.

8. It is not uncommon for certain state-owned enterprises to be bailed out of bankruptcy for the 7th or 8th time.

9. Wang, R. S., Hongzhun, R. & Ouyang, Z. (eds.) China Water Vision: The Eco-Sphere of Water, Life, Environment and Development (China Meteorological Press, 2000)

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Huang, Y. Q. ‘From Work-Unit Compounds to Gated Communities: Housing Inequality and Residential Segregation in Transitional Beijing’ Restructuring the Chinese City: Changing Society, Economy and Space, Laurence J. C., Ma and Fulong Wu (eds.), Routledge (2005)

13. Urban Heat Islands occur when a city full of blacktop and concrete absorbs and re-releases significant quantities of solar radiation. Greenery absorbs this energy and also, through respiration, keeps an area cooler.

14. China Statistical Yearbook, 2005.

15. Cole, B. ‘“Oil for the Lamps of China”—Beijing’s 21st Century Search for Energy’ McNair Papers, U.S. National Defense University, (Washington D.C., 2003)

16. Wang, R. S., Hongzhun, R. & Ouyang, Z. (eds.) China Water Vision: The Eco-Sphere of Water, Life, Environment and Development (China Meteorological Press, 2000)

17. Luo, T., Ouyang, Z., Wang, X., Li, W. Carbon Discharge through Municipal Solid Waste in Haikou, China (forthcoming 2006)

18. Rice production is one of the biggest culprits in agriculturally driven C02 release.

19. Norton, Bryan G. Sustainability: A Philosophy of Adaptive Ecosystem Management (University of Chicago Press, 2005) p. 360

Pondering the Green Edge*

Erich Schienke talks with Neville Mars

ES: What were the issues concerning you when you started the designs for the L-building and for the GBD Art and Design District?

NM: As a foreign designer working in China pushing a progressive sustainable agenda is one of the few added values we have to offer. China’s impressive green ambitions for 2020 have produced an array of studies, suggestions and guidelines aimed at reducing emission levels. This is important, but the magnitude of China’s problems demands a more profoundly integrated approach. And China, as it will double its building stock over the next two decades, has this unique opportunity. At the outset of what is potentially a green revolution it is essential to aim for more then reducing the environmental impact with a myriad of greenification gimmicks. To achieve this, I believe efforts should include both ends of the scale, now largely ignored — the regional and the individual.

My concerns on the regional scale relate to the increasingly suburban landscape that is forming. We have coined the term splatter pattern* to describe the vast urban expansions taking place at village-level. Based on the premise that a significant proportion of future consumption is already determined once land use and urban form has been designated, this will constitute highly inefficient urban regions. The harsh reality China has to face is that even a collection of good green buildings can deliver a bad city. The anxious socio-economic context facilitates the almost instantaneous shift from a red to a green society — at least on paper. But coherence between the sea of new building projects is much more difficult to realize.

ES: What about individual level problems facing greening in China?

NM: About the problems at the individual scale I am less skeptical. A green society is not the product of laws and guidelines alone. The individual, or rather the consumer, will define the success of most green ambitions. Like so many aspects of China’s modernization it’s the combined result of top-down government interventions and bottom-up incentives that generate the hyper-speed transition. China’s double-digit economic growth can be argued to be at a standstill when the environmental squalor costs an estimated 10% GDP annually. At the same time air pollution is directly affecting the health of millions of individuals. According to the Chinese Academy on Environmental Planning (2003), air pollution is the cause of 411,000 premature deaths every year. This is particularly poignant when you consider that the average individual in China consumes only a fraction of what people in most Western countries do. We are faced with a rather paradoxical aim in terms of greenness: less to reduce individual consumption, but to serve and stimulate future green consumers.

Chinese society is in the process of a complete transformation. The objective is to accommodate the xiao kang* or well-off middle class in a new urban environment by 2020. This means we have to conceive what the urban environment should be now. Though cities like Beijing seem to be modern, in reality they are realized with just another upgrade of a monotonous housing stock. High-end green efforts are mostly aimed at prestigious office towers and tend to overlook the challenge of the explosive residential realm. In crude terms the housing program can be reduced to dormitory extrusions* and villa parks. As the Chinese home consumer diversifies this monotony will be disastrous for the lifespan of a notoriously short-lived housing-stock. Having completed a brand new* urban environment at the scale of Europe in two decades, China would have to start all over again, green buildings or not.

Ultimately the individual and regional scales affect each other. China has embarked on a social revolution that can be summarized as a shift from a single society of radical equality to a radically segregated society. The scattered urban landscape that is forming is defining the modern Chinese way of life. For those who can afford it, this equals a car-dependent suburban lifestyle. While mass-consumption is on the rise for some, dismal conditions remain for many. Greenification schemes are mostly up-market, simply pushing primitive conditions to the edge of society. The fact that China has ventured on a path that is not socially sustainable will hinder its ambitions for environmental sustainability.

ES: I agree that a massive transformation is underway, but within the context of Chinese history neither inequality nor difficulties of scale are in themselves new. Do you put the radical aspect of these changes down to speed and the numbers involved, or is there a fundamental morphological change happening? If the landscape is undergoing complete transformation, are traditional and even current forms being lost?

NM: Traditionally Chinese cities were compact clear centers in the landscape. Even during the twentieth century cities did not expand beyond the reach of the bicycle. The neighborhood was integrated; work and living were closely aligned. Though not sustainable in a modern society this presents an ideal configuration on both the scale of the region and the individual home. Even today for the 200 million households that don’t have running hot water, economizing on energy is painfully easy; more so for the 20,000 villages entirely cut off from the grid. Ironically the lack of the most basic amenities and infrastructure has accelerated the spread of sustainable technologies. China is the world's largest producer of solar panels, and the number of people still off the grid have made it the world’s largest consumer. In the countryside a staggering 50 million collectors have been installed. However leapfrog developments have uprooted the urban fabric on many levels. The compact city and the social setting of the traditional neighborhood are all but lost in the expansion of the Chinese suburb.

China’s hukou* registration system divides the population into two distinct groups: urban and rural. This suggests two distinct spatial conditions: the city and the countryside. However the predominant development occurs on the threshold of these two and produces nothing more than a rurban* landscape — an indiscriminate fusion of rural and urban elements that lacks the qualities of either condition. To gain a grip on the landscape at least three basic conditions should be distinguished: rural, urban and suburban. The suburbs and the suburbanite define the residential median of China’s expansion. It is the most dynamic zone, with potentially the largest impact on the environment. Here the values of the traditional neighborhood and the compact city should be reintroduced.

ES: And so the suburbs are the “Green Edge*” your designs refer to?

NM: Originally the title of our research, the Green Edge*, was a cynical reference to one part of Beijing’s greenification scheme: a project that has edged major roads, particularly around international tourist attractions, overpasses, and the international airport expressway, with a thin sleeve of trees, plants and flowerbeds. In a notoriously dry city, this seems to be a water-thirsty fauna offensive to make Beijing look green from a car, while blocking the view onto dilapidated neighborhoods around the Third Ring Road. But we felt this name was more appropriate for the zone around cities with the particular green potential we have distinguished in our urban proposals*. The objective for this zone was to define the edge of the city in order to tackle sprawl. It became clear in China that the suburb has to be given a second chance — if only because of its success.

At the moment the Chinese suburb is no more than an indiscriminate region where fortunate home-owners, the forcefully relocated, and ever more middle-class citizens are finding refuge. The trend itself is thoroughly global — people either want to live in the suburbs or can’t afford to live anywhere else. But here, for young real estate refugees*, the flight to the suburb is the Chinese Dream*. It too has its roots in an economic revival and the success of mass-consumption and individual transportation. But the Chinese suburb is still distinct from its American counterpart. The Chinese suburbs still contain real social diversity and a variety of spatial conditions. This may be only temporary though, as an unseemly form of over-planning* dominated by highways and industrial parks is pushing small-scale developments out to the periphery leaving behind a sterile and inaccessible landscape. Still I feel there is hope. Unlike American suburbia, the Chinese suburbs often present remarkably compact building typologies. This is a potentially invaluable condition that China should nurture to give quality to its urban periphery. Paradoxically urbanization, mass-migration and population growth can help to elevate the suburb to become an integrated part of a compact metropolitan environment.

To achieve this, suburbia should be confined to clear boundaries. Where suburbia starts and stops however is hard to define. We have suggested any urban expansion beyond the reach of high-end public transport should be considered unsustainable. The zone within the mass-transit system which is not part of the center we have coined the Green Edge*; a transitional zone between the city and the countryside. Freed from its derogatory appellation and its image as a refuge for rich and poor, this part of the suburb can take on the role of being the city’s green heart, accommodating a rich mix of social classes, densities, urban functions and green space. The Green Edge* introduces a highly sought after urban quality: lush residential environment with fast access to the center.

a collection of green buildings won’t necessarily make a green city

绿色楼宇的堆砌未必是绿色城市

ES: But aren’t suburbs normally perceived to be at the heart of the sprawl problem, rather than the green solution?

NM: True — we are claiming green building projects belong in the suburbs of large cities — and we are aware that this statement is counterintuitive. China is currently in the grip of a satellite fetish*. Somehow with satellite towns suburbanization is not a concern. Building more satellites and celebrated concept towns should compensate for the inexorable expansion of China’s semi-industrial, semi-modern, semi-urban landscape: the satellite town has become the focus of an eco-exodus.

And in principle it can work. China, the world’s most sophisticated developing country has signed a contract to build the world’s first completely sustainable city near Shanghai. Engineered by Ove Arup & Partners and located on an island it should be a successful, truly autonomous green city. However, most likely the countless other green planning projects will be less comprehensive and less autonomous. They will induce sprawl and demand longer commutes instead of enhancing the semi-developed periphery. This is why green projects belong in the suburbs, or rather the Green Edge*.

The eco-exodus and the concept of a sustainable satellite are not new. They are reminiscent of the ideologies of New Urbanism (NU); a movement which proclaimed the invention of a socially refined, walkable eco-town of human proportion with historical trimmings back in the eighties. However as a socially environmentally sustainable vision NU and its offspring Smart Growth are impaired by their car-dependency and price tag. Their walkable qualities entail only the stroll from the house to the church and the barbershop. They lack the critical mass* necessary to support high-end transit to the workplace. In addition they build on what was previously open space. This reduces New Urbanism to a gated community without walls; the result of carpet planning* with stylistic cues. Its most prominent examples — Celebration, Seaside, and The Glen — are tantamount to a privatization of public space at the town-wide level and create an encapsulated town rather than a mixed, interactive community. Without the conspicuous walls of the Chinese condo their privacy depends on isolation, gentrification, and citizens’ decrees. Some of these are light-hearted enough — for example in Celebration it’s officially not permitted to be unhappy — but for China the success of 20,000 gated communities in the US presents a rather less frivolous scenario. As China progresses most likely similar desires for a neo-suburban lifestyle will burgeon. In the dichotomist Chinese environment, compounds sealed off from society threaten the durability of the suburb. The split cities* they produce prohibit the assimilation of migrants and low-income citizens into the suburban society.

ES: Okay, so tell me a little about the specific history of the actual designs themselves.

NM: Well, our first large urban commission in China was surprisingly progressive. We met a developer who from a commercial standpoint supported our ambitions for sustainability and urban diversity. The assignment was for an art and design district in Gao Bei Dian (GBD); an area of rapid change in east Beijing near the Fifth Ring Road. We felt this was a good example of the kind of space we aimed to capture with the Green Edge* concept. The area is a leftover plot wedged between highways, train tracks, and semi-urbanized villages*, but with impressive green features.

In the first stage the project was intended to be purely an art district with large art studios, loft apartments, and galleries and offices for the creative sector. As you know in Beijing recently dozens of areas have been designated for the creative industry*; sometimes this is an effective method to elevate suburban areas struggling with their industrial heritage. But often it’s merely a government label void of real meaning, and applied to postpone any clear decision. This put us on the spot to answer the question if an art district could really be designed — would this kill the grass-roots qualities? Should artists be left to find urban niches themselves, as they have done successfully across the globe? Art districts come and go and nowhere faster than in Beijing, and this is only normal. But in Beijing they develop under strangely contradictory forces. Some like Dashanzi 798 have been acknowledged and flourish; others have been painfully short-lived and leveled without notification. This constant threat made us decide that a well-planned creative district which would provide individual artists with a safe environment in which to live and work was worthwhile.

But as the project evolved so did the assignment and even the actual site conditions. The reality of our central hypothesis of dynamic density* became all too apparent. Our challenge for the two designs we had made was to develop systems that would be flexible, yet diverse and detailed. The level of detail expected in a Chinese urban proposal approaches the architectural scale, and this unfortunately eradicates most flexibility from the design process. I believe this is one of the reasons why in China instant designs are commonplace. Our efforts to achieve extreme flexibility allowed us to safeguard the search for creative solutions. The systems we’ve engineered can withstand continuous alterations while maintaining their principle qualities. The two systems presented here are based on organic principles: one a backbone, the other a cell pattern*.

ES: And how does this work out spatially?

green buildings belong in the suburbs — or rather, the green edge* of big cities

绿色建筑只存在于郊区,或者说是大城市的绿色边缘

NM: The backbone or Strip* evolved from our desire to connect to the urban network via a public space at a time when the majority of real-estate projects turn away from the public domain. Providing a space that offers both circulatory and locational qualities can be the basis for a dynamic and diverse street life. The reality of the Beijing suburbs, however, literally left us looking for loose ends to connect. The project site is naturally as cut-off from its surroundings as any walled community. In response we have designed a single strip that is both origin and destination; a distinctly urban zone that forms the backbone for urban development in one direction, and a clear demarcation from the surrounding ecological park in the other. These two aspects of the project — city and park — work together as one ecological system that channels water flows and preserves energy. The ecological park replenishes the consumption of the urban strip. The park is a showcase for environmental design and encourages green consumers. The surface of the urban strip is almost entirely permeable and tapered to distort the perspective*. From each end the total distance looks either very long or very short. Visitors are naturally drawn deep inside the area and then persuaded to wander around through the park.

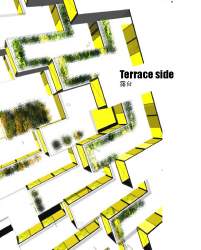

The buildings are wrapped along the central axis or vista and connected by a continuous tensile sun-screen that protects the pedestrians against the hot Beijing summer. The built volume slopes down to offer maximum penetration of sunlight and an enhanced view over the park. Sustainable projects are generally only open to the south, but art studios require northern light. This provided an interesting opportunity to develop an intricate roofscape. Jagged strips of industrial style light wells cut through the entire district. The windows face north, the south facing facades are covered with solar panels, the flat parts become terraces and walkways, the soft slopes are covered with vegetation. The natural qualities of the site have been enhanced with indigenous plants and natural installations such as the solar aquatic system* and reed beds.

Then the assignment grew, the site parameters shifted and the project gained a large amount of commercial and leisure program. The network of paths and designated routes we’d planned through the site became much more elaborate, while the available surface decreased. It’s an obvious solution to rely on tall structures to comply with Chinese building codes, and admittedly there are strong incentives behind the suburban skyscrapers we see emerging. But developed as single mega-compounds these environments more often resemble a form of Chinese Modernism* — large blocks on a map of endless undefined cross-hatched grass; an urban approach which is leaving neighborhoods oddly inaccessible behind vast empty spaces. Within the context of the Green Edge* we proposed to aim for a low-rise solution without compromising the density.

Using cantilevers, bridges, decks, skywalks and extensive sunken retail streets and squares the available space is greatly increased. Cars are removed from sight and the distinction between above and below ground, the street and the terraces is permeated. To achieve this, a formula was created for a single cell of 2,500m2 to be developed by a single architect. These cells are then grouped together to form larger patterns which can adapt to specific conditions such as trees or a river. The Chinese puzzle pattern of plazas and corridors is the result.

ES: Your proposals speak also about the social aspects of the design, suggesting even a resonance with ‘communist principles’, and offering a ‘soft transition’ from hutong* to skyscraper. How do you reconcile this with the market’s current fetishization of the new and apparent unconcern with demolishing previous environments? Communism in China has demonstrated a capacity to engage successfully in large-scale development projects, but this has not always produced an integrated approach to urban design.

NM: If you look at things over a slightly longer term, there is absolutely no contradiction between marketability and social concerns for the user community. The L-building* is an architectural response to our research at the individual scale. Green projects, and particularly housing, need to be marketable. We feel that an increasingly critical consumer of living space will not accept the plastic-wrapped boxes on offer today much longer. A housing stock that offers greater diversity with preferably more comfortable homes is in itself more sustainable. This means part of the problem is purely architectural. I realize this is a direct critique of the design education in China that still has not been able to adopt a more conceptual approach, let alone nurture the creativity of its students, but sustainability, marketability, and attractiveness ultimately all combine to form a triple bottom line for any development.

The letter L in L-building embodies these qualities. L is the primary shape of the apartment, but L also stands for Luxury and for Loft. We have designed the units as lofts not merely as the epitome of the architect’s dream apartment, but as a space that can easily be adapted from one owner to the next. The apartments can be either completely compartmentalized or entirely open, and thus can be made suitable for couples, small families, or a new generation of single occupancy tenants born out of the one child policy.

The L-building as a whole introduces the further aspect of social sustainability, often missing in China and in the general discussion. Nothing is more desirable than an apartment with amenities such as running hot and cold water, a toilet, and a view. But for the inhabitant the transfer from the ping fang* — the simple derivative of the famous hutong* — to the modern tower block is often less rewarding as time goes by. The traditional Chinese neighborhood, including the danwei*, had an exceptional social coherence. Qualities of the ping fang* that were taken for granted, particularly the sense of community, are disappearing. Recreating a community for the individual within an environment of large-scale developments will become increasingly important in China, as more and more people find themselves not only relocated, but also questioning the benefits of that relocation.

Both the GBD Art and Design District and the L-building mediate between China’s traditional urban environment and the contemporary trend of up-scaling*; between low-rise and the modern tower block. First the L-building complies with some rudimentary suburban desires — a large private garden and your car at the door. But as a medium-sized, collectively developed, owned, and operated form, 1 the L-building also resonates with more traditional principles.

ES: Traditional principles as in the courtyard?

NM: Yes. It seems a contradiction and failed attempts prevail, but the Chinese courtyard or siheyuan* can be stacked. As a hybrid between a high-rise and a hutong*, the L-building retains the three essential qualities of a sizable garden, close connection to the neighborhood, and privacy. This is achieved by fusing the typology of the patio with terrace housing. The long walls of the immense terrace function as a courtyard on your rooftop. The protruding semi-cantilevered gardens catch the sun even when it sets behind the building. Walking to the end of your terrace you overlook the neighboring gardens, the park and the surroundings.

Note

1 The development model for the L-building draws on the capacity of the many dadui* in the suburbs to realize their own buildings on their own land.

Owned by neville mars / Added by Stephanie Yao / 18.6 years ago / 75349 hits / 11 hours view time

Backlinks

Tags

Latest Entries

Contribute

Login to post an entry to this node.