United Mumbai

Project team for MARS Architects / DCF: Neville Mars, Anitra Baliga, Etienne Mares , Yuval Zohar, Lin Jun**

Prototypes of change for BMW Guggenheim in Mumbai

This page is dedicated to the proposals developed by MARS Architects for the the BMW Guggenheim Lab Mumbai, a mobile laboratory traveling to cities worldwide. Its goal is the exploration of new ideas, experimentation, and ultimately the creation of forward-thinking visions for city life. Not often does a small planning studio get the opportunity to reimagine a megalopolis. But with scale comes responsibility. The contributions of MARS Architects are based on the premise that a minimum amount of private space is crucial for the individual to flourish, while a minimum of public space is needed for the city to operate efficiently. While hyper dense Mumbai ranks amongst the lowest in the world on both fronts. An integrated urban vision has been developed that unfolds on the scale of the individual through product and technological developments, but steadily expands to have a city-wide impact on urban efficiency and sustainability.

During the year-long project, comparisons between China and India have triggered many discussions. Specifically Shanghai’s expanding skyline, seems to have mesmerized policy makers to look for a planner’s silver bullet, such as another viaduct or sprawling fly-over. In reality, the only denominator the world’s most populated nations have in common is a proclivity for heavy-handed planning solutions. As Mars explains in this video introduction, India’s Prime Minster's ambitions to make Mumbai like Shanghai by 2020 typifies top-down approach, which, though partially successful in China, will be hard to emulate in a democracy, let alone in a metropolis where two-thirds of its population is living in slums, invisibly scattered across its entire cityscape.

Instead, bottom-up strategies have proven to be effective, at least on a local scale. The challenge has been to embrace the vibrance and resilience of informal communities as a starting point for a citywide sustainable vision, aligning the multitude of local efforts with formal networks, connecting different scales, communities and technologies.

~ SOCIALLY AND SPATIALLY THE SLUMS HAVE REACHED A POINT WHERE THEY MUST BE EMBRACED AS SOPHISTICATED MICROCOSMS ~ NEVILLE MARS

.

As the public events of the BMW Guggenheim Lab Mumbai draw to a close, MARS Architects is proud to announce the opening of its Mumbai satellite office from where we will work with local partners to implement a number of the proposed designs. These pilot projects represent a dramatic shift in how sustainable technologies and design can be integrated within a bustling city, crippled by pollution, poverty and urban fragmentation, bypassing a planning system defined by political inertness and skewed public funding.

MANIFESTO UNITED MUMBAI

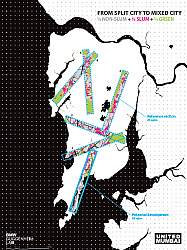

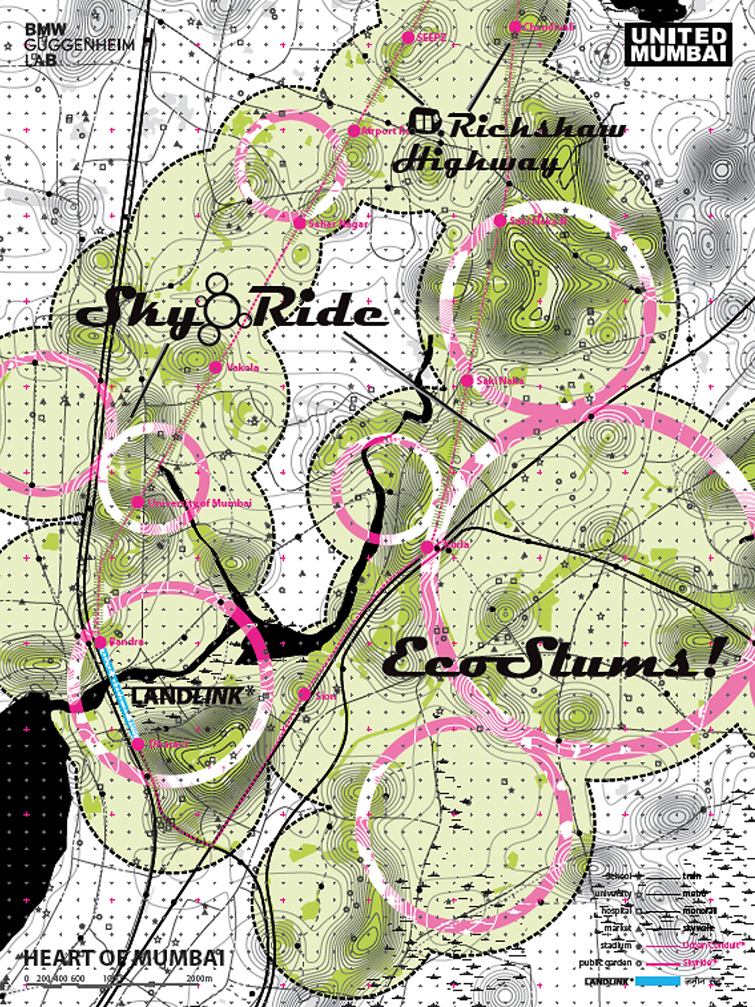

With Manifesto United Mumbai, MARS Architects has developed an ecology of solutions that address the most urgent issues from access to drinking water, to public space and transportation. Implementation occurs through a generational approach. Individual technologies evolve to become increasingly sophisticated and connected, supporting each other, in order to survive in a context where minimum space remains and all renewal projects operate at either end of the spectrum, exacerbating what can only be defined as a SPLIT CITY*.

The WATER WALL* and GROOVE* are low-cost building components that work together to make rainwater harvesting feasible within slums. Combining living roofs with efficient water storage, daylight and comfort are brought to hot dim-lit slum dwellings. The WEATHER TAP* is a hybrid installation adapted to Mumbai’s extreme climate. Alternating between rainwater collection and sea water desalination it provides fresh water all year round. Steadily, the water deprived slums can become independent in their fresh water supply, reducing pressure on the city's strained infrastructure.

Water, sanitation and waste managment form the cornerstones of sustainable informal settlements, or ECOSLUMS*. Counterintuitively, it is in the slums where investments in sustainability will have most impact, both on the quality of individual lives and citywide sustainability, at least if this strategy can be expanded across the city. By spatially connecting the informal settlements, they can begin to work together, sharing resources and opening labor markets. The HEART OF MUMBAI*, a cluster of informal settlements of over six million inhabitants, steadily converts into a green hub in the geographic center of the city.

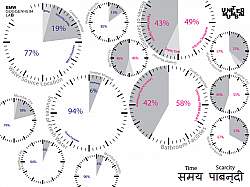

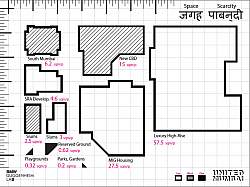

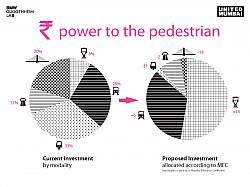

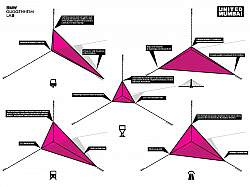

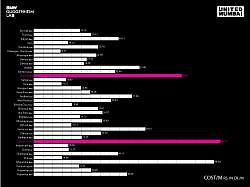

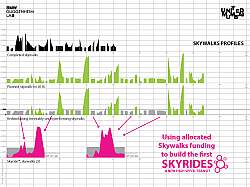

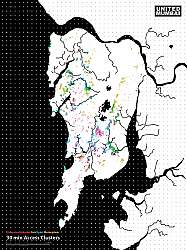

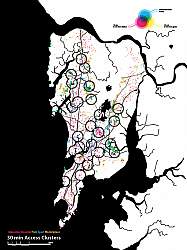

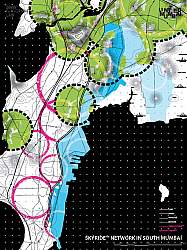

Improving access to public resources (as measured by new more human-centric indices that incorporate both TIME and SPACE*) will define the success of Mumbai. However, it is clear forging new connections will be difficult. Public space per capita ranks amongst the least in the world, while congested roads distort the perspective on the transit woos, soaking up funds for the 3% of commuters in private cars, while leaving pedestrians stranded on poorly accessible and primitive skywalks. The SKYRIDE* adopts the simple technology of the skywalk to offer dedicated double elevated decks for bicycles and rickshaws, that bridge the gap between the main transit lines and the densest communities with door-to-door connections.

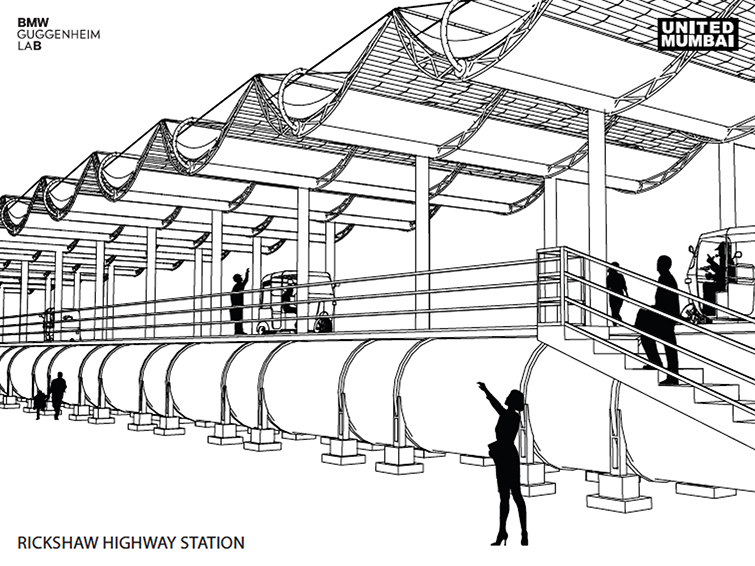

Reclaiming the space of the soon-to-be-defunct Tansa water pipeline, a RICKSHAW HIGHWAY* is proposed that cuts through the entire north-east of the island city. The Weather Tap provides the roof structure of the stations generating electricity to power the rickshaws. Adopting COLLABORATIVE PLANNING*, a grand public plaza is envisioned as its terminus station. The LANDLINK* forms the foundation of the world’s first slum CBD, linking two of the city’s major slum areas and opening up a large nature reserve that now divides North and South. One slum at a time, the informal settlements join to form a single urban entity, with a single voice and equal position in Mumbai’s urban and social fabric.

In ten workshops with stakeholders, local and international planners, designers and scholars these pilot projects have become the new planning principles of MANIFESTO UNITED MUMBAI*.

SPI MODEL

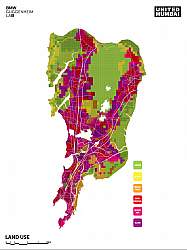

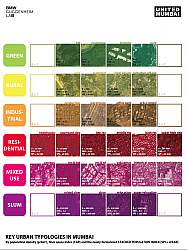

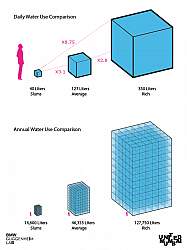

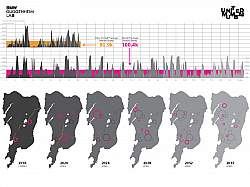

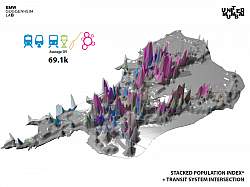

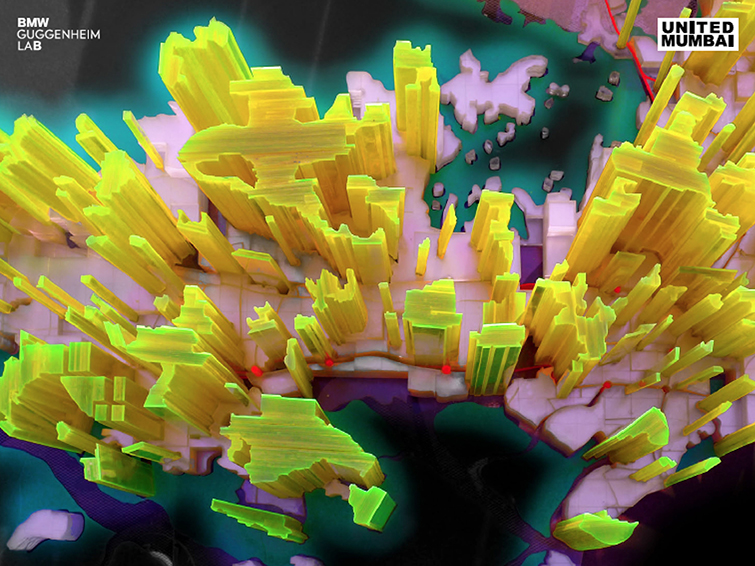

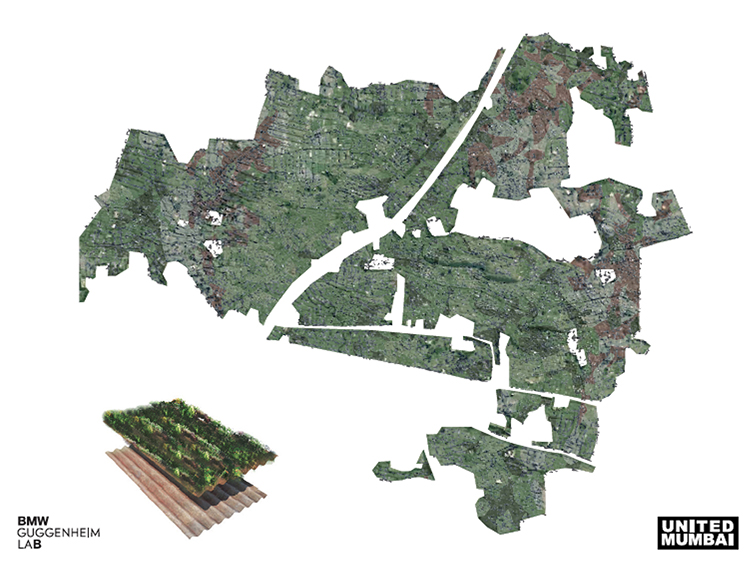

The foundation of this project is an in-depth study of Mumbai’s population density. Not merely mapping Mumbai’s infamous conditions in abstract terms but introducing a new methodology that better represents the experience on the ground. The new metric, called the Stacked Population Index (SPI), measures the density of people per amount of available floor surface to produce a measure that reflects the experience of density by calculating the actual built surface area of living space available for individual Mumbaikers in different areas. Suddenly the true extents of Mumbai’s informal settlements can be observed: a yellow forest of towering densities dominating the entire urban landscape. A radical reality of a city that accommodates two thirds of its population on less than a quarter of a its urban space.

There are 13.34 million in Mumbai's Island City, resulting in a massive density of 36,200 people in each square kilometer. This density is particularly constant across this central area of Mumbai, where the architecture consists of a contiguous patchwork of medium-height, mixed-use building structures. However, what makes Mumbai's urban morphology truly unique is the omnipresent informal settlements woven throughout the urban fabric, which comprise 20 percent, or 74 square kilometers, of the city’s geography—yet accommodate as much as 65 to 75 percent of the population. These settlements are largely limited to low-rise structures that on average are not taller than two stories, meaning those areas have a high density of tightly packed inhabitants.

To make this information more accessible and better representing the experiential aspects of the population densities on the ground, MARS Architects has developed a new index of population density based on Floor Space Index (or, Floor Area Ratio). Using satellite images to create a detailed map of the building typologies across Mumbai Island City, this methodology examines the average density in gridded map cells of 500 square meters, based on occupancy rates for each of the 28 specific typologies. These numbers form the basis of a new index, dubbed “Stacked Population Index” (SPI) by incorporating the Floor Space Index (or, Floor Area Ratio) for each cell.

项目基于我们对孟买人口密度的深入研究。我们不仅仅是用抽象的方式将孟买的糟糕现状绘制出来,而且通过引入一套新的方法,让我们可以从地面上直观地感受这些讯息。这种新的度量方法叫做人口堆叠索引(SPI),它能够测量出每个可用地表上的人口密度。我们可以迅速获悉整个孟买非规范性住区的真实分布程度:一个高耸繁密的黄色森林占据了整个城市景观。在这片茂密森林的背后是一个残酷的事实:在一块不到空间四分之一的区域里容纳着整个城市三分之二的居民。

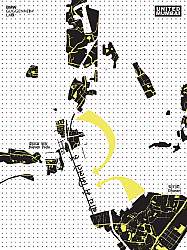

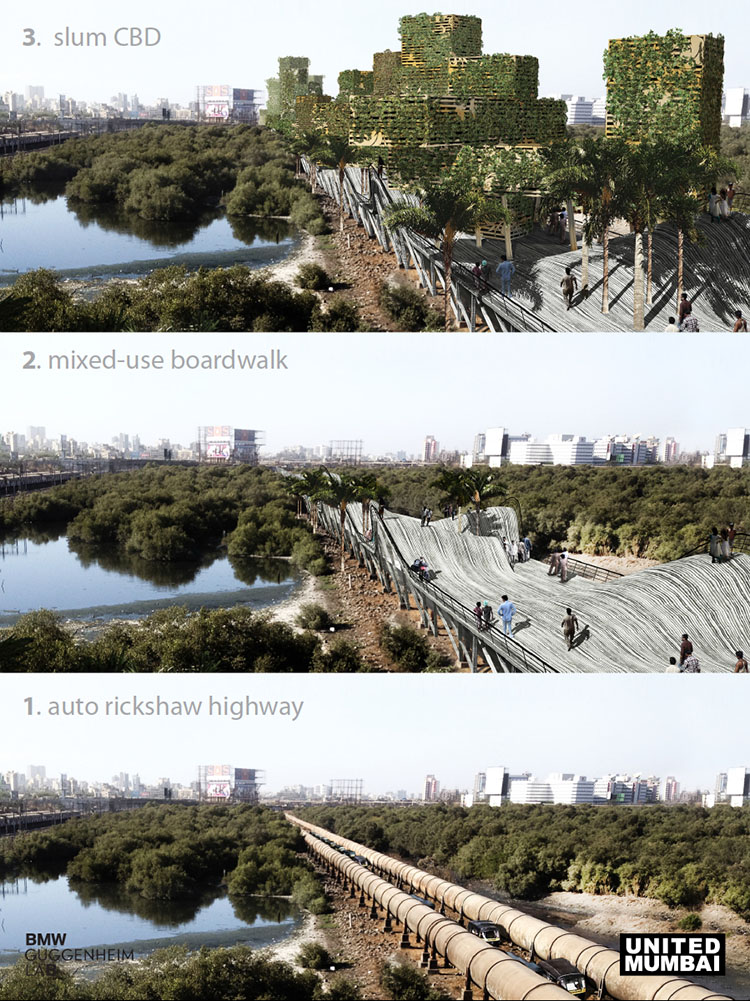

The LANDLINK*

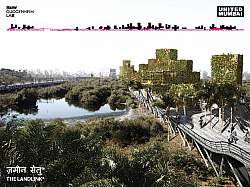

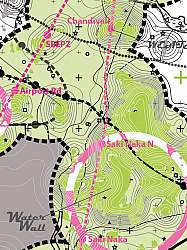

The Landlink* is an answer to Mumbai’s infamous Sea Link and the first prototype to tackle Mumbai's time-space conundrum. In contrast to the Sealink, it provides pedestrian, bike and rickshaw connection between two of the city’s main slums by readopting (soon to be) outdated pipeline infrastructure. The Landlink crosses a famous mangrove lagoon, revealing it as a large park in the heart of the city while providing space for public functions that cannot be accommodated in the compact surrounding settlements.

The proposal aims to inspire new possibilities with existing infra-space. Located on top and between two soon-to-be-defunct water pipes, the Landlink* becomes a multilayered bridge that facilitates transportation, public and commercial activities, and social engagement in an area that is now deprived of larger communal spaces. In a gradual collective effort between local communities and city officials, commercial and non-commercial parties, the bridge achieves its full potential. The Landlink* starts off as a line for bicycles and rickshaws, then evolves into a pedestrian deck and commercial plaza, and finally supports small towers to become the world’s first slum CBD.

Public space, commercial space, and transit space have historically been bundled together. But in Mumbai’s crowded streets, this condition has reached a tipping point. The Landlink* aims to provide ad hoc market spaces that are adjacent to, but don’t impede, flows of pedestrians. The different conditions the pipe encounters as it cuts through the urban fabric generate opportunities to refit the old infrastructure with new functionalities, opening visual connections to the natural landscape, bringing access to remote areas and connecting slums to each other.

Excerpts of the interview on the pipeline by Christine McLaren:

The Landlink* is a provocative statement about beginning to use what Mars calls “infraspace”—the space taken up by infrastructure alone. “Any space currently used solely for infrastructure in Mumbai is so often just taken over by other activities —whether [they are] commercial, or leisure, or praying, or whatever—and we can really learn from that. I think from highways to pipelines to flyovers to train tracks, all these spaces make up a vast amount of area in Mumbai that has potential to be redeveloped in an interesting way because there is no other land. So it’s almost about indicating how you can have multiple functions, multiple program[s] stacked on the same purpose, and then the obvious choice is this infraspace,” he told me as we walked.

Continuing, he said, the proposal is a counter-move to the highly controversial Sea Link bridge—a costly development directly adjacent to the Landlink route that connects south Mumbai to north Mumbai by rerouting cars around the city’s congestion via a toll bridge that juts out into the water. “We’re suggesting that instead of linking, let’s say, formal acknowledged city to formal acknowledged city, we should start linking slums. Slums make up the majority of the people in the city, and they are becoming increasingly mobile. They need connections. They need forms of getting around. If we’re moving toward a middle-class situation, mobility is key,” he said. And naturally following that: “It shouldn’t be about cars, obviously, it should be about high-speed local transport.”

THE LANDLINK* MODEL AT THE BMW GUGGENHEIM LAB IN MUMBAI

Lab site photos: UnCommonSense © 2013 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

TIME and SPACE SCARCITY

Mumbai, melting pot of disparate rhythms and flavors, religions and cultures seems to defy logic. Models fail and visions disintegrate, yet Mumbai thrives. Confronted with harsh social divides and sharp spatial contrasts, both the city and its citizens have found ways to adjust and adapt to a severely compressed urban condition. Still expanding on its seven fused islands, Mumbai’s public spaces are squeezed into tiny alleys and spill over into large highways, while private space for most citizens is reduced to a mere state of mind. Yet it’s obvious any traditional perceptions of private and public must be abandoned as these concepts constantly morph into each other, to the point that, in Mumbai, 'me turns into we'. This project sets out to describe this dazzling dance of adaptations that allows productivity amidst chaos, pleasure amongst the crowds.

But it’s a precarious balance, when many basic human needs are squandered. And the city, while thriving, is throbbing with congestion and pollution. The public domain, the institutions (tangible and non-tangible), infrastructure and public space that constitute the essence of a city remain in disrepair. The amount of public space per person is amongst the lowest in the world, as is public investment. With close to 90 percent of employment as part of the informal economy, the city’s facilities and utilities only cater to those who can afford them. Like a medieval capital, the countless cultural, religious and political events slowly snake through the bustling streets, and most commercial activity washes out onto the pavement with the monsoon floods.

As we chart these tensions across the city’s private, public, transient and mind space, the limits of both individual comfort and urban efficiency come to light. With each layer added to its tangled future, Mumbai will need to reinvent itself to offer new spaces, new forms of collaboration and collective organization. With a crippled public domain, can Mumbai really thrive, or merely cope to survive?

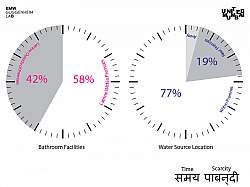

We have coined two new terms that seek to capture the way technical and structural aspects of Mumbai’s landscape affect individual Mumbaikers everyday lives. First, 'time scarcity,’ relates to the time people spend in order to have access to basic services, utilities and resources. A major problem in Mumbai, where the poorest residents must give up considerable amounts of time to accommodate in their most basic needs, time scarcity impedes opportunities personal growth and self-development. Second, ‘space scarcity,’ measures the actual free space citizens have at their disposal when both private space and (accessible) public space are mapped for a specific individual. In space-scarce Mumbai, notions of what is public or private space shift constantly, demanding a new measure to describe the amount of space Mumbaikers can call their own throughout the course of the day.

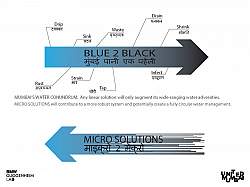

BLUE TO BLACK

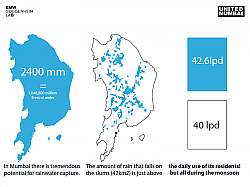

For Mumbai water is probably the best example to illustrate that a linear approach to solving a dense complex metropolis will ultimately fall short. From depleted reservoirs and dropping water tables, to unsafe drinking water and lack of sanitation, to surface water pollution and degraded public space the issues surrounding water in Mumbai are all directly related. Currently the end result is simply: blue water in, black water out. It is clear only an holistic approach can begin to address the systemic problems. This means top-down infrastructure must be supplemented with local micro-scale solutions.

Every year after the monsoon, Mumbai is concerned if the rains have replenished the reservoirs sufficiently, and every year the concern becomes more acute. To meet the growing demand an increasingly large network of pipes is being built to connect to further outlying lakes. Still, demand is always greater then the supply and drinking water shortage and impurities impact on the daily routine of the majority of the population. This top-down technocratic approach to meeting demand, is not only insufficient, it defines the borders of what the ecological systems of Mumbai can suffer.

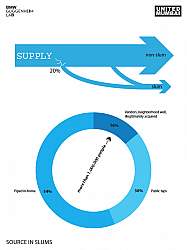

The current supply is 4.2 billion litres per day of which 3.3 reaches the consumer, while the rest is lost through leakage or illegal tapping.

As much as half a million people in 21 slum communities across the city are subjected to severe water crisis. The ongoing lack of access to a steady water supply prevents the installation of sanitation and sewage treatment for as much as 70% of the population.

Rainwater harvesting though an official regulation is not enforced. Desalination, which would be an option but is deemed too expensive. However, we believe that the core problem is an outdated linear approach. Could solutions of local water harvesting, local storage and filtration bring affordable potable water for all around the clock within reach?

In Mumbai city, if eighty percent of rain water on all the terraces is captured, it will yield more than 500 mld water. A serious contribution to the flushing need (40 liters pcpd) for which untreated rainwater can be used. Though mandatory for building projects larger than 1000 sqm, storage of Mumbai’s monsoon concentrated downpours remains a serious challenge. Several water harvesting projects have gained little support. Conversely, rain water harvesting on roofs of slums only could fully cover the entire water demand in slums.

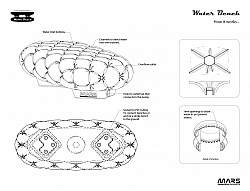

THE WATER BENCH - NEW!

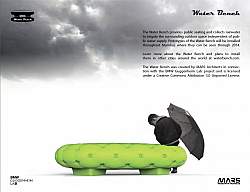

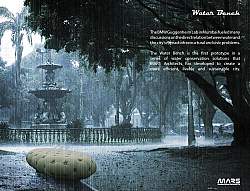

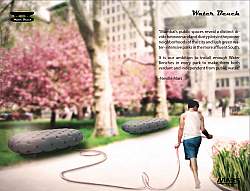

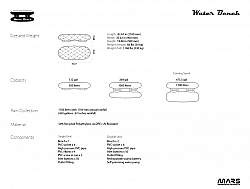

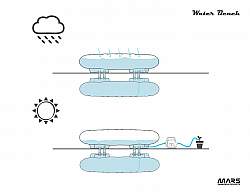

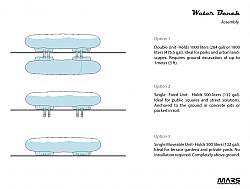

The Water Bench is outdoor furniture that collects and stores rainwater through functional cushions. Created as a response to Mumbai’s water woes, it is the first mass-produced installation that is implemented as past of the long-term urban vision which MARS Architects was commissioned by the BMW Guggenheim lab. Inspired by Chesterfield sofas, these benches create an atmosphere of an urban living room in public areas, featuring an easily adaptable modular design. Currently being field-tested in Mumbai, the water collected in the Water Bench is used to irrigate parks and green spaces in order to relieve pressure on public water sources.

“水椅”是一件用于采集和储存雨水的城市家具作品。作为何新城建筑事务所与宝马古根海姆实验室合作的城市可持续发展战略中的第一个大量生产的装置产品,该设计便是为了缓解孟买日益严重的水荒问题。灵感来自英国古典切斯菲尔德长靠椅沙发,“水椅”作为一个易于调节的模块设计,在公共空间营造出城市客厅的氛围。 近期“水椅”在孟买进行了系列现场试验,成功采集到雨水用于灌溉植被和绿化,减轻了一部分的公共用水负担。

Water is our most essential resource; yet it is increasingly synonymous with inequality, disease, and environmental degradation. Demand for water continues to increase drastically, not only for drinking, but also for sanitation, manufacturing, leisure, and agriculture. The emergence of water-dependent urban landscapes is of great concern in developing economies. Urban green space often consumes great amounts of water and yet, is integral to providing healthy and liveable cities.

Encountering this conundrum, we have sought to provide a range of local solutions, designed to be networked together into larger systems, capable of taking pressure off already strained centralized infrastructures. The Water Bench is the first prototype in a series of small-scale solutions that together can produce a big impact. It was designed in line with a new approach to urban design that emphasizes multi-functionality and sustainability. The Water Bench embodies this new vision by combining standard outdoor furniture with rainwater collection and storage to create a product that increases water independence at the local level while providing an attractive place to sit and socialize. The Water Bench is a micro-level innovation that fits within a new, decentralized approach to water management, capable of immediate implementation across the city. Far from being finite, the Water Bench is part of an ecology of solutions with the potential to be implemented in a variety of contexts. It is the first of hopefully many small-scale interventions we have developed that together, can help reconfigure urban areas relationships with water.

The Water Bench is an ideal standalone installation for small plots and private gardens. At the scale of the city, however, we have always considered the Water Bench as part of a larger group of water conservation solutions. To build an integrated water supply system we envision central and decentralized parts to work together at the neighborhood scale. Combined with water run-off and smart wells they can make parks and public spaces independent from district water supplies. These solutions work to lower demand, increase supply and create buffers to minimize the impact of floods and droughts. Together they complete the traditional infrastructure and make for a much more resilient and flexible water management system.

The Water Bench, made from partially recycled polyethylene, is a modular design using the same mould for the underground and above ground tank. Its design is inspired by Chesterfield sofas: the aesthetic of eighteenth-century-style upholstery becomes functional as the grooves and seams in the seat guide the water to the buttons, which act as water inlets to tanks inside the hollow bench. In this way, the surface remains dry for sitting, bringing the comfort of an urban living room to outdoor public spaces. With three different storage capacities—500, 1,000, and 1,800 Liters—the benches fit different urban scenarios and site conditions ranging from terrace gardens to public parks. The smallest unit that doesn’t require groundwork is best equipped for roadside installation; the medium size has an underground tank, ideal for gardens and greenhouses; and the Iargest unit is best suited for public parks and playgrounds. The first Water Benches have been installed in Mumbai’s Horniman Circle and Cross Maidan for a one-year prototyping phase, starting at the beginning of monsoon season.

Learn more about the Water Bench project at www.WaterBench.com

“涟椅”设计,是由何新城建筑事务所与宝马古根海姆实验室的合作为期一年的产品开发项目。该项目设想:通过针对当地城市资源问题的解决方案,来建立一个规模较大的城市可持续发展系统。水源供应管理的问题上,整合资源尤为重要,从饮水、卫生到农业,水都是不可或缺的重要资源。在这份报告中,何新城先生将会阐述不同的解决方案如何相互融合、整合联系起来,以应对这样一个人口密集的城市背景所带来的可持续发展的挑战,为目前的焦点问题——“新兴经济体中至关重要的集中基础设施建设”提供了一个可能性。

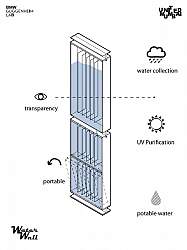

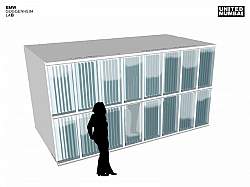

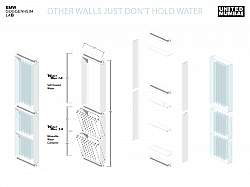

The WATER WALL

The consequences of the water availability and quality issues that plague Mumbai tend to land on people in the slums. Therefore, these solutions are developed for and will be tested in slums. A range of microsolutions that deal with water collection, purification, and local storage can level the playing field by making the slums water-independent. As Mumbai decides desalination is not affordable solution, we offer localized alternatives that brings this option within range. Currently, slum dwellers mostly have two water containers in their home: one containing water from a public tap is used for washing and cleaning and a smaller one with water for drinking and cooking that is typically bought from a water truck. Water storage is critical if Mumbai is to embrace rainwater harvesting. The Water Wall aims to save space by storing water within the cavities of a structural and modular wall system that is connected to the roof and has different compartments for washing and drinking. The translucent tanks allow daylight to penetrate the mostly dark and dingy homes.

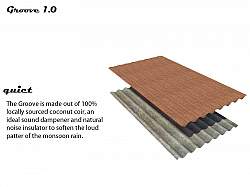

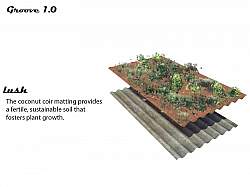

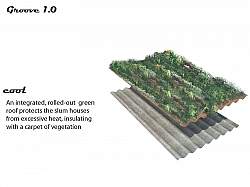

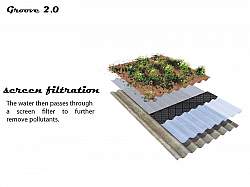

The GROOVE

The two weather conditions typical of Mumbai’s climate make the living environment in slum dwellings unnecessarily uncomfortable. During the dry months it gets terribly hot, while the monsoon rains loudly patter on the corrugated roof plates.

The Groove 1.0 is a simple roof mat that unrolls to fit the grooves of Mumbai’s omnipresent corrugated panels. Made of local coconut coir, the mats are extremely affordable and fully recyclable. The Groove dampens the loud clatter of the monsoon and cools indoor temperatures during the summer heat. As a solid root bed for plants, these qualities only improve, while the neighborhood starts looking green.

Extending the functionality of the Groove, the Groove 2.0 introduces three separate water-cleaning segments. Apart from rainwater harvesting, piped water- which is currently far from potable- runs through a set of natural filters that remove harmful particles through phyto-remediation, then water undergoes UV disinfection as the final step in becoming potable.

GROOVE 3.0: TASTY TRAYS

Flexible and light urban farming solution above ventilated storage space.

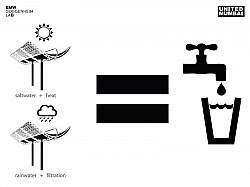

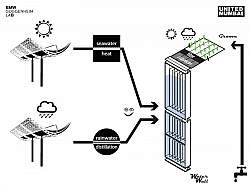

The WEATHER TAP

Mumbai’s water supply is dwindling, while demand is growing. In recent years, pipelines have been pumping water from more and more remote reservoirs, and yet, an average monsoon will not sufficiently replenish them for the following year. As a result, flow is intermittent, distribution unequal and quality very poor. It is clear that local water systems will be needed. Plenty of rain falls on Mumbai, the challenge is that it all falls for just three months. The Weather Tap is an affordable and scalable solution that collects solar energy in the dry months and harvests rainwater during the monsoon. Collected rainwater is filtered to become potable, while solar energy that is collected is used to desalinate sea water into fresh drinking water, resulting in a continuous local fresh water supply all year round.

The RICKSHAW HIGHWAY

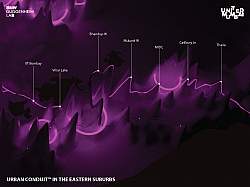

Over 55 kilometers long, the Tansa Pipeline cuts through Mumbai passing a variety of environments. What starts with the Landlink* extends beyond Mumbai Island connecting poorly accessible urban areas to the transit network, while offering goods and logistical connections between highly productive slums in the center and large industrial suburbs. The Rickshaw Highway is a proposal convert unused infrastructure into a localised transportation network for autos and bicycles by adopting the interstitial spaces of these existing pipelines. This could connect poorly accessible urban areas to the transit network while offering links between highly productive slums in the centre and large industrial suburbs.

SKYRIDES

Mumbai’s transit network is steadily expanding. Bursting train carriages are testament to the need to bring more people efficiently to and from the suburbs. Local transportation, however, is still underdeveloped. Transit lines cut through areas of extreme population density without offering direct access. Auto Rickshaws bridge this gap and provide millions of people with cheap and fast home-stretch transportation. Despite being barred from South Mumbai, the rickshaw is a crucial and sustainable component in the city’s transit equation. The Skyride adopts the simple technology of the Skywalk to offer dedicated two level elevated decks for bicycles and rickshaws, connecting transit infrastructure to where the people are. Together, the Rickshaw Highway and the Skyrides complete Mumbai’s formal transit system with high frequency, cheap, and local commuting options, taking pressure off Mumbai’s stressed transit corridors and providing better access to areas of extreme population density.

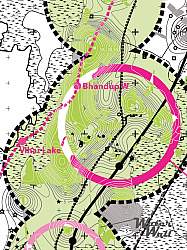

The HEART OF MUMBAI

As Mumbai becomes increasingly polycentric, the new centre of urban gravity has moved north to the Mahim area which has the potential to become a new Heart of Mumbai, a green and highly accessible hub that can help decongest South Mumbai.

The Heart of Mumbai concept aims to forge connections between North and South Mumbai; formal and informal areas. It promotes the geographic centre of the island as a strategic hub for future development with great potential for access to public space and amenities.

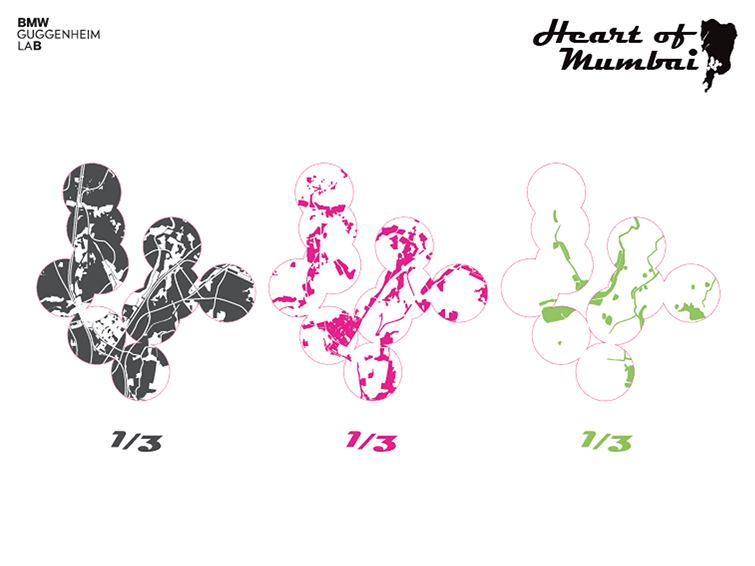

COLLABORATIVE PLANNING

The Municipal Corporation is now preparing the city’s next development plan, scheduled to run from 2014–2034. We suggest that planning must be coordinated collectively and reflect the different solution components in equal measures of 1/3 formal development + 1/3 informal development + 1/3 green and open space. However ambitious this land-use formula may seem, our research shows that this configuration has evolved in many patches across the island, as the below images indicate. As Mumbai’s Eastern Wharf becomes available for development, a profound opportunity for a fully holistic planning approach presents itself. By creating a typology that combines extreme population density with an impressive built volume and much needed open space, Mumbaikers can have their cake and eat it too.

MANIFESTO UNITED MUMBAI PRINCIPLES

Manifesto United Mumbai addresses the relationships between Mumbai’s urban morphology and its unique socio-cultural context, such as it fluid notions of privacy and public space. After the various research projects we can conclude that Mumbai should be understood as a highly fragmented urban landscape, both spatially and socially. Half of the population, scattered across the entire metropolitan area, cannot equally partake in the formal part of the city and its public facilities. Though omnipresent, the slums remain invisible in the minds of planners and policymakers alike. Large-scale top-down conceived projects, such as transit lines, utilities and public spaces, both fail in their effort to address the many pressing issues and to reach the population in equal measures. This amounts to different forms of time-poverty, or the reduced access to public amenities and space and its consequential impact on private time. As a result, opportunities to experience privacy in its most fundamental form (as measured in terms of space and time-scarcity) are severely diminished. Simultaneously, the many micro-scale efforts to improve slum conditions fail to align with higher-scale ambitions and remain ad hoc.

Working on the intermediate scale, the steering committee and action group of United Mumbai work together to offer concrete proposals to bridge these gaps, that are translated to proposal proposals. The detailed maps that have been produced trace how the fragments of informal settlements can best connect to infrastructure in order to reach the densest moments in the urban fabric and reach more people more efficiently. Technical solutions, or prototypes, will be further developed to make the informal city more autonomous with regards to water, food and energy needs.

The ultimate goal will be to spatially and technically patch the many plots together and grant the informal city equal access and an equal position in the urban layout. This requires a new collaborative approach to planning. The Land Link offers a first concrete step towards connecting Mumbai at the neighbourhood level. In the Meet in the Middle public program, these design proposals have served to ignite discussions on how to achieve a collaborative approach by engaging stakeholders at different scales. The outcome is a planning manifesto outlining the guidelines for pilot projects to be abide by.

Manifesto United Mumbai is a set of six principles formulated to guide action towards a more efficient, livable and sustainable city. These principles are the result of in-depth research and extensive expert and stakeholder meetings aimed to pinpoint caveats and obstacles in current planning and define workable solutions. GOAL: Spatial integration is the main objective in order to improve the overall cohesion of the city and ultimately arrive at a United Mumbai.

1. MEET IN THE MIDDLE

United Mumbai will be the result of collaborative planning. The first principle demands for each United Mumbai project stakeholders commitment of community representatives, NGOs or private entities and government representatives in an equal capacity. GOAL: Nurturing public-semi-private partnerships and new business models viable within the unleveled playing field of Mumbai.//

2. BRIDGING THE GAPS

United Mumbai projects must operate at the intermediary scale, bridging the gaps between conditions on the ground and top-down planning projects – as reflected in the discrepancies between public investment and demographic representations. This demands detailed mapping of existing conditions and should foster a stronger role for the Ward Sabhas.

Goal: Initiating local projects that can be scaled up in order to impact the city-wide level.

3. COMPRESSING MUMBAI’S TIME-SPACE CONTINUUM

Accessibility is the main criterion to quantify and evaluate United Mumbai proposals. However, evaluation can no longer occur merely from an engineering perspective, but must incorporate the social and individual perspectives. Time-scarcity and space-scarcity are two measures that proposals will be compared with, bridging the technocratic and human-centric approach. GOAL: Promoting solutions that increase the access to public utilities and facilities, public space and transportation.

4. HOMEGROWN URBANISM

Western notions of planning have proven inadequate within the harshly fragmented urban context of Mumbai. United Mumbai projects acknowledge the resilience and richness of organic urban fabric and embrace home-grown solutions as viable urban strategies. GOAL: Promote projects that nourish localized efforts into sustainable settlements as the seeds of city-wide sustainability.

5. SCENARIO-DRIVEN / VISIONARY

The MiM workshops have underscored a concern for the practice of post-planning, which leaves Mumbai perpetually catching up with reality. United Mumbai aims for future proof solutions and underscores the importance of long-term, ambitious and visionary objectives. GOAL: Promoting vision-based projects and scenario-based planning to achieve a value-driven development plan.

6. PARALLEL PATHS OF PROTOTYPES AND POLICIES

Initiatives that are solely policy-driven have proven to be toothless within the pragmatic context of Mumbai. United Mumbai calls for parallel multi-disciplinary collaborations around producing strategic prototypes at neighborhood levels. The pilot projects lay the groundwork for policy level proposals. GOAL: Testing viability of policies by implementing tangible proposals through public-private partnerships.

STACKED PANEL SYSTEM

The United Mumbai Panel System is a design project that can be experienced at the main Lab site at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum. The Panel System is in interactive installation made specifically for the Guggenheim Lab. It consists of seven parallel tracks along which three groups of transparent maps slide. This produces a possibility to combine the maps in hundreds of different configurations.

The project provides a tool for stakeholders and local community members to discuss and analyze the fine balance between the public and the private, and collectively draw up a new plan for a “United Mumbai”—the city-to-be that addresses the needs of all its citizens. The mechanism for this conversation involves a series of panels divided into themed sections—such as infrastructure, resources, and public space—superimposed on maps of Greater Mumbai. By overlaying the different panels on top of each other, visitors can examine and discuss what it would take to build a comprehensive and efficient urban network for the future of Mumbai.

MEET IN THE MIDDLE public forum

In this hands-on, interactive workshop lwith key practitioners in Mumbai (PK Das et al.) and leading scholars in the field (Saskia Sassen, et al), we've explored new ways to connect transport, water, and housing infrastructure. Stakeholders, community leaders, NGOs and officials converse how the different urban concepts and prototypes can become a reality for Mumbai. The forum aims for a much vaunted, yet seldom observed holistic approach to the many profound challenges which the city of Mumbai faces, by mediating its public and private contingents to arrive at a new center that bridges micro and macro scale planning efforts, connects top-down and bottom-up infrastructure projects and unites public and private stakeholders. Over the course of the Lab's stay in Mumbai, visitors and participants to the “Meet in the Middle” sessions will also jointly form an steering committee for collaborative planning—a manifesto of a United Mumbai.

Program series initiated by Neville Mars. Facilitated and co-hosted by Naresh Fernandes and Sourav Biswas. The ten MIM sessions covered the following topics:

Split City Mumbai

Mumbai is a city of vast divides, where the quality of services depends on where you live.

Participants: Amita Bhide, Chairperson, Center for Urban Policy and Governance, TISS; Aisha Dasgupta, Fellow, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Mumbai Lab Team member; Shilpa Phadke, Chairperson, Center for the Study of Contemporary Culture, TISS; Anita Patil-Deshmukh, Executive Director, PUKAR; Kalpana Sharma, writer/journalist, "Rediscovering Dharavi;" Asif Zakeria, Corporator, Ward H-West.

Rethinking Skywalks and Sealinks

Mumbai’s thirty-six skywalks have been the subject of heated debate. This session explored the qualitative potential of the Lab’s proposed networks of landlinks and skyrides, and critically examined how investments in transport through car-oriented sealinks and pedestrian-oriented landlinks/skyrides could be made for Mumbai’s future.

Participants: Rishi Aggarwal, Fellow, ORF; Trupti Vaitla, Urban Designer, MESN, Mumbai Lab Team member; Mustansir Dalvi, Faculty, JJ College of Architecture; Prasad Shetty, Founder, CRIT; Rupali Gupte, Faculty, KRVIA; Shivjit Sidhu, Partner, Apostrophe.

Mediating Public–Private Housing

Fifty-two percent of Mumbai’s residents live in slums, yet the city has recently seen the construction of its first gated communities.

Participants: Neera Adarkar, Architect and Urban Researcher, Adarkars Associate; Alexis de Ducla, Project Head, Lafarge Affordable Housing; Matias Echanove, Director, URBZ; Avijit Mukul Kishore, Documentary Filmmaker, "Vertical City;" Rahul Srivastava, Director, URBZ; Vishnu Swaminathan, Director, Housing for All – Ashoka India.

Mediating Public–Private Transportation

Mumbai’s trains are overflowing and its roads are jammed. In this panel discussion, we will explore how to balance the need for more public transport with the demands of those driving private vehicles.

Participants: Madhav Pai, Director, EMBARQ; Geetam Tiwari, TRIPP Chair, IIT-Delhi, BGL Advisor; Ashok Datar, Chairman, MESN; Sudhir Badami, Independent Transportation Consultant; Nitin Dossa, Chairman, WIAA; Rachel Smith, Transportation Planner, AECOM, Berlin Lab Team member.

Heart of Mumbai Workshop - Bridging the Infrastructure

Participants: Akshay Mani, Project Manager, EMBARQ; Roshni Udyavar, Head, Rachna Sansad; P.K.Das, Founder, Architect-Planner, Open Mumbai; Rohan Shivkumar, Deputy Principal, KRVIA; Kayzad Shroff, Partner, Shroff-Leon; Nicholas Humphrey, Emeritus Professor of Psychology, LSE, BGL Advisor; Rachel Smith, Transportation Planner, AECOM.

Planning in a Dynamic City

While the Mumbai Municipal Corporation works toward framing its twenty-year development plan in 2014, experts explained their vision of collaborative planning for Mumbai and how it can be achieved.

Participants included Prathima Manohar, Founder, Urban Vision; Sam Lockwood, digital strategies consultant; Henk Ovink, Deputy Director General Spatial Planning, Ministry for Infrastructure and the Environment, Netherlands; Shirish Patel, Planner, IIHS; Pankaj Joshi, Executive Director, UDRI; and Uma Adusumilli, Chief Planner, MMRDA.

Participatory Planning

The Municipal Corporation is preparing Mumbai’s next development plan, scheduled to run from 2014–2034. This panel discussed the citizen’s role in government development and participatory planning in Mumbai.

Participants: Vinay Somani, Founder, Karmayog; Milind Mhaske, Project Director, Praja Foundation; Chetan Temkar, Founder, Smart Shehar; Shailesh Gandhi, RTI Activist, Former Information Commissioner, Government of India; Prasanna Desai, Principal, Prasanna Desai Architects; Gautam Patel, environmental lawyer; Himanshu Burte, Architect-Researcher, TISS.

Mediating Public-Private Investment

How do we incentivize public-private partnerships that operate across different social scales?

Participants: Ashok Datar, Chairman, MESN; Cyrus Guzder, Trustee, BEAG; Madhusadan Menon, Chairman, Micro Housing Finance Corporation; Arun Nanda, Director of Mahindra & Mahindra and Chairman of Western Region-Confederation of Indian Industries (CII); Ajit Ranade, Chief Economist, Aditya Birla Group; V. Ranganathan, Chairman Mumbai Heritage Conservation Committee and former Urban Housing Secretary and Municipal Commissioner; Saskia Sassen, Lynd Professor of Sociology and Member, The Committee on Global Thought, Columbia University.

Me=We Memorandum

At the end of six weeks of looking at specific areas through the Meet in the Middle series, select participants from previous discussions returned to frame a manifesto for Mumbai and bring suggestions to the table.

Participants: Neera Adarkar, Architect and Urban Researcher, Adarkars Associate; Ashok Datar, Chairman, MESN; Aneerudha Paul, Principal, KRVIA; Prathima Manohar, Founder, Urban Vision; Brinda Somaya, MD, Somaya and Kalappa Associates; Narinder Nayar, Founder, Mumbai First; Rohan Shivkumar, Deputy Principal, KRVIA; Sam Lockwood, digital strategies consultant; Gerson da Cunha, AGNI Governance.

All design content on this page is developed by MARS Architects and curated by David van der Leer as part of BMW Guggenheim Lab Mumbai.

MIM and on site Photos: UnCommonSense © 2013 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Owned by neville mars / Added by neville mars / 16.9 years ago / 96938 hits / 7 hours view time

Tags

Latest Entries

Contribute

Login to post an entry to this node.