Taobao / Urbanity Unhinged

THE EDGE OF THE CITY

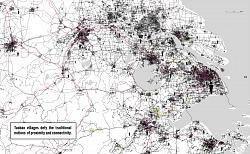

There is no countryside. Rurality is dead. The Chinese hinterlands have been consumed by ever present urbanisation. In many places, the rollout of urbanism has engulfed villages into its folds or simply bulldozed what remained of traditional villages. In some cases, the “villages” have been relocated, meaning the occupants moved into a housing block and the historic built environment destroyed. Sometimes, the physical villages remain as traditional buildings — surrounded not by a scenic landscape, but rather high rise apartment blocks.

In the Chinese imagination, rurality features larges. There are constant conversational references to one’s village, even if that village is now a city of millions. Where one is from is immensely important. The mountains, plains, steppes, lakes and forests feature large in pastoral portrayals of the country. The village is imagined to be situated in a natural landscape straight out of a brush painting. The agricultural heritage of the nation is remembered in direct relation to the village typography. The countryside is painted as a harmonious relationship of people, agriculture and nature. Chinese tradition is rooted in village life, from familial structure to cultural holidays. In modern China, not just culture and imagination tie people to rurality, but hukou binds people to the place of their heritage. As a country deeply rooted in spatial locality, rurality is a large portion of contemporary discourse.

The imagination of rurality continues to be enforced. There is the promise of untouched natural landscapes. But in the tightly woven urban webs of what was once countryside, the most rural environments are the preserved historic villages, locked in time, upgraded, polished, and presented as what the dreams of rural China ought to hold. Renting costumes, performances of traditional art forms, and cute cafes all paint the village as modern escape from the city. But across the canal or outside the wall, there is no picturesque countryside, rather urbanism is pressing in from all sides.

In place of the village — where the countryside once was, where agriculture and nature were not mutually exclusive, where there were pockets of human life instead of pockets of natural life — now there is grey. In this new state, everything is connected, urban is ever present, nothing remains untouched. The village is interwoven, nebulous, invisible. Rurality is a debilitated construct.

THE TAOBAO VILLAGE

The Taobao Village killed rurality. Taobao markets the idea of the ‘Taobao Village’, an entity that has some semblance of coherence. As of August 2016, Alibaba has recognized 1311 villages both in areas classified as ‘rural’ and ‘urban’. But where the village has diffused into the urban landscape, what is village and what isn’t is illusive. Taobao’s reach to the most granular level of human habitation, the remote village, has eliminated the last possible distinction between urbanity and rurality. Taobao thrusts material urbanity onto the doorstep, into the shed, through the mailbox of every last nook and cranny of settlement.

The Taobao Village killed rurality. Taobao markets the idea of the ‘Taobao Village’, an entity that has some semblance of coherence. As of August 2016, Alibaba has recognized 1311 villages both in areas classified as ‘rural’ and ‘urban’. But where the village has diffused into the urban landscape, what is village and what isn’t is illusive. Taobao’s reach to the most granular level of human habitation, the remote village, has eliminated the last possible distinction between urbanity and rurality. Taobao thrusts material urbanity onto the doorstep, into the shed, through the mailbox of every last nook and cranny of settlement.

Yet, in some ‘villages’ where Taobao activities are thriving, there are minimal traces on the ground that Taobao is taking hold. Taobao’s ground level effects are radically reorganising the economic logic of what was once the countryside, without necessarily having an exaggerated impact on the built form. This isn’t to say there aren’t places where the inflow of Taobao hasn’t changed the physical and imagined structure of space, either creating zones of e-commerce or weaving a network of Taobao shops in amongst existing commerce and residences. In either of these cases, it is common for Taobao to have drastic effects on how villagers understand the space of the village.

But even without rebuilding the physical village, Taobao is entirely reconstructing rural life. The ‘ding’ of orders coming in at every hour of the day has overthrown historic rhythms of life. Village units struggle with the introduction of competition that tugs at their social fabric. Generational gaps in internet literacy transform power dynamics both in local leadership and within the family. However, the economic opportunity Taobao creates in the countryside draws migrants home, bringing families back under one roof, allowing more in tact family units. This has repercussions for gender dynamics, where women are rejoining family enterprise, or alternatively returning to more traditional gender roles in positions of care-taking, reconstructing family structure that was disrupted by migration patterns, creating the potential for either empowerment or regression.

COLLAPSING THE HIERARCHY

The global urban fabric has been arranged in a hierarchy. Isolated cities once dominated the functional landscape. Cities as centers of trade, socialization, and creativity were the forces that drove the world forward. Yet in the age of global urbanization, this model has disintegrated. Even in an increasingly dissolved state, the traditional city hubs have functioned as the highest and most important nodes in the global geopolitical landscape. As the primary centers of production and consumption, cities created the logics that have circumscribed global patterns. The metropolis is built on the greek concept of the polis: a political, negotiated spatial entity that requires compromise for the benefit of all. The core of the city has always been the market, once physical, now extrapolated into the economic definition of the city. The polis, the place of exchange has stood at the peak of urban hierarchy, leaving the hinterland in less powerful geopolitical positions. The value of spaces near to sites of socioeconomic importance is a vital logic of spatial development. Von Thünen’s model of outwardly decreasing assignment of land value has been extrapolated such that the conception of unequal value of place has infiltrated every nook and cranny of the city, and has in different forms, become the guiding discourse of urbanization. Unequal value of place is the logic that determines rent gradients, drives development from housing and transport planning to industrial zones, and ultimately values the city above the countryside. But Taobao collapses the hierarchy. The polis, the place of exchange, is deterritorialised. Everything is equally accessible everywhere, so the logic of unequal value of place crumples. The immediate availability of goods and services along with the colocation of consumption and production nearly flattens the hierarchies that have defined the gradient of rural//urban.

URBANITY UNHINGED//RURAL RESURGENCE

Economic prosperity in the countryside is growing while individual heritage and roots continue to loom large in Chinese daily life. Economic draw to the countryside is spreading, with more job opportunities being created in the countryside. At the same time, family ties and lineage generate a strong pull back to villages. Returning to the village offers “the reappearance of intact family units and the rekindling of family emotions, self-esteem, a sense of freedom and accomplishment in young people”.

Economic prosperity in the countryside is growing while individual heritage and roots continue to loom large in Chinese daily life. Economic draw to the countryside is spreading, with more job opportunities being created in the countryside. At the same time, family ties and lineage generate a strong pull back to villages. Returning to the village offers “the reappearance of intact family units and the rekindling of family emotions, self-esteem, a sense of freedom and accomplishment in young people”.

While at the same time, in cities, cost of rent impedes interest in work, increasing pollution clouds heads, and the ever more fragmented urban landscape fails to inspire. Isolation in some of the worlds biggest cities is common, and “With the rapid increase of living costs in urban areas, urbanism [has] imbued a sense of modernity’s rootlessness in young people, thus producing exhaustion with and alienation towards urban life”. Cities no longer glisten brightly as heliographs pointing towards a better life.

The right to migrate to the countryside, both for returnees and opportunists, is essential for China’s sustainable development. Although never formalized, an ability to leave the countryside must now be complemented by an ability to migrate away from cities. The right to the countryside incorporates not just movement, but also imagination. As Lefebvre conceives of it, the right to the city is the right to change ourselves by changing the city – as the countryside is increasingly urban, this rings as true in every small village as in the most massive of megalopolises. The right to the countryside is the ruralised right to the city.

In a country increasingly obsessed with materialism, access to the consumption and production of goods has helped expand the Chinese middle class to a size that only recently would’ve been an outlandish dream. Eager to expand their sales, e-commerce companies search for the last remaining untapped markets, namely the most remote potential sites of consumption: the rural landscape. While initial efforts to connect to these outlying rural tracts to e-commerce focused on consumption, another major trend emerged: colocated production and consumption. The most powerful and effective has been Taobao, a peer-to-peer platform that allows vendors to sell directly to consumers. Taobao can act as a means of empowerment, allowing rural villages to create opportunity and access to wealth through freedom of production, allowing villages to diversify their economic activities, previously only possible in already well connected cities.

Taobao villages were initially an effort of interested villagers looking for ways to improve their economic conditions. Villagers saw the potential in selling their goods through Taobao sans middlemen, allowing them to collect a greater share of the profit. Setting up Taobao shops has fairly low barriers to entry, attracting sellers and encouraging a diversity of shops. Taobao villages connected through the ruralurban interwoven economy gather gravity about them, attracting more services, lowering the barriers to entry, nurturing more shops throughout the village. In some cases this is production of goods that villagers already have familiarity manufacturing, while in other cases this offers an opportunity to enter new fields. Farmers can sell their produce online, often through voluntary agricultural local online collectives, earning 10 times the amount they would earn selling the same crop or product through the standard supply chain. Logistics, service industries, creative industries, as well as new forms of production all are springing up in Taobao villages, fostering multitudes of generativity and incentivising migration. While parts of the ruralurbanisation movement are driven directly by villagers, this is in collaboration with the pluralities of urban actors in China’s developmental systems. In the context of the Taobao village, the framework of top-down/bottom-up is mostly irrelevant. The local government may work closely with the blossoming shops to create service centers, while Taobao itself may make local interventions, putting pressure on governments and developers to create better infrastructure. E-commerce is restructuring the process of urbanisation at a fundamental level by leveling the hierarchy of economic connectivity between cities and these far-flung locales that are now woven into the urban economy.

TAOBAO = ENERGY

While the virtual realm collapses distance and thereby the urban hierarchy through incredible interconnectivity, it comes at a cost. The built structures that prop up the virtual realm have drastic environmental effects. The infrastructure required to move parcels, people, and raw materials at light speed consumes vast amounts of energy. Near instantaneous transportation across the country relies on China’s vast coal capacity to power its electric trains, and petrol and diesel to fuel the vans, trucks, and scooters that weave the virtual network into the physical. In order makes the new virtually interconnected yet physically dissolved urbanity efficient, we must deploy the strategies of good planning. As urbanity spreads ever further, environmental degradation claws at China’s remaining natural systems. Locally informed, cross-scalar, sustainable planning must to deployed in the face of these seemingly insurmountable environmental challenges. At the very core of our assumptions of sustainability is compactness. All efficiency is derived from compactness, and all the work of this book works towards this end. While the countryside through new virtual urbanisation is disintegrating any semblance of compactness, we introduce strategies to pursue this ideal that is always just out of reach.

Owned by neville mars / Added by neville mars / 9.9 years ago / 4723 hits / 3 minutes view time

Tags

Latest Entries

-

Taobao

-

Internet Plus - foreword of the book "Internet Plus: From IT to DT" by Jack Ma,

-

The Tetralogy of Village Taobao’s Business Model

-

Interview with Sheng Zhenzhong from Aliresearch, Jul 19th, 2015

-

An Overview of County-region Economics from the perspective of “Internet+”

-

Summary of China’s E-Commerce Business Park Development Report (中国电子商务园区发展报告)(2014-2015) Part 2

Contribute

Login to post an entry to this node.