Masterplan Pudong 2040

A vision of constraint

english PDF

I. EVOLUTIONARY PLANNING 进化的策略 • SCALE+SPEED=COMPLEXITY 尺度+速度=复杂度

• A CROSS-SCALAR STRATEGY

• MEDIATING SPATIAL DEMANDS

• THE BENCHMARKS OF MEGACITY

• EVOLUTIONARY PLANNING

• SPACE/TIME/RESOURCE ECONOMY

跨尺度的策略

中介空间的需求

巨型城市的标准

进化的规划 空间/时间/资源 -经济

METHODOLOGY

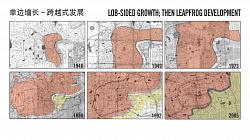

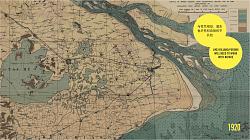

In the early 80s, Pudong was conceived as a grand futuristic vision for a city ready to embrace moder- nity and and reclaim its role a global economic powerhouse. The time had come to take the leap of faith across the wide Huangpu River and make up for Shanghai historically only developing Puxi, or its “west shore”. Projected on the empty farmlands of Lujiazui, the sharp indentation in the Huangpu River offered Shanghai the rare opportunity to profoundly reimagine the very heart of the city, complete with a dramat- ic new skyline perfectly positioned to be gazed at in awe from the banks of the old Bund.

As we set out to envision the long-term future of Pudong, observing its basic genesis offers important in- sights into its current urban composition. Spawned from this single ostentatious seed, Pudong expanded southwards, converting farmland at breakneck pace. Ring after ring of dense residential districts were draped around the central business district, in order to accommodate Shanghai’s exploding population with modern apartments.

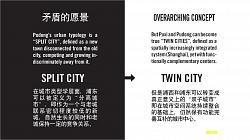

SPLIT CITY / TWIN CITY

In under two decades Pudong has grown to a size that can measure up to the historic heart of Puxi. This extremely rapid expansion has generated radically different conditions, illustrated by perfectly apposing spatial qualities and a functional mix on either side of the river. Although in most ways complementary to each other, Puxi and Pudong do not form a integrated whole that makes up contemporary Shanghai, but rather have remained spatially disconnected and largely competing entities. Without careful infrastruc- tural integration their rapid expansion in opposite directions will enforce the development of increasingly insular entities, along the lines of a SPLIT CITY model.

MARS Architects offers a vision that aims for a shift towards a TWIN CITY model as the basis of an integrated Shanghai consisting of two distinctly different but complementary halves. As part of a TWIN CITY Pudong should be able to operate independently, while spatially growing towards the center along its transit corridors.

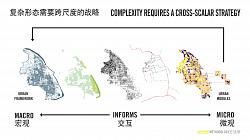

COMPLEXITY

The sheer scale of Pudong and the astounding speed of growth that has shaped the larger region, to- gether have generated a unique challenge: spatial complexity.

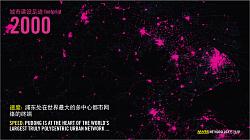

SCALE: With over 5 million inhabitants on 1300 sqkm Pudong is both in size and population the largest district of Shanghai, which in turn is the world’s largest — and by some measures the densest — city proper. Stretched out over 70 KM, tip to tip Pudong’s elongated district can be crossed within a two hour subway commute.

SPEED: Hyper accelerated expansion defined urban growth across the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) since the turn of the millennium. In just ten years the total footprint of the region’s intricate polycentric network has exactly doubled. The predominant typology of this flash urbanization is a dense and often monotonous road-oriented suburbia, not unlike what we find across Pudong.

COMPLEXITY: Pudong can quite effectively be dissected in layers of urban, suburban, industrial, port, rural and natural areas. However, although these programmatic zones are easily distinguished from each other, they are increasingly blurring with the rural landscape and informal industries to produce an amalgamation of highly contrasting functions and spatial conditions.

Much of the urban fabric of Pudong is either dense but monotonous or diverse but granular — i.e. coarsely assembled, disconnected and unrelated. The increasing pressure to develop, combined with the difficult to regulate this muddled spatial condition has steadily eroded the protected productive land unique to Pudong.

EVOLUTIONARY PLANNING

Our vision for Pudong requires a shift towards community oriented planning with a strong emphasis on inclusive, mixed-use and green neighborhoods. Operating on a complex morphology this is easier said than done. A cross-scalar, time-based approach, or what we call “Evolutionary Planning” becomes es- sential. This concept is in line with the former vice-director of MOHURD Mr Qiu Baoxing central theme of ‘complex systems’. This entails a more holistic approach that acknowledges that many factors that influence the formation of the city are well outside of the territory of planning. It suggests that the com- plexity that is the hallmark of a healthy city cannot effectively be planned — while most planning efforts achieve the very opposite. We must concede as planners we need recalibrate our role. First, any long- term vision can only unfold gradually over time, and many unknown factors will impact its realization. As such Evolutionary Planning does not offer a spatial blue print, but rather a set of tactics designed to anticipate constant adaptation to changing conditions on the ground.

Second, at the regional scale we must prioritize spatial decisions — rather than say technological ones. As these will forge many of the urban patterns that in turn will define commuting times, energy and land use patterns, and so forth, for decades to come. Even the ability to adopt new technologies relies on a timely allocation of space.

Our strategy unfolds along three growth scenarios. However, even in a ‘zero-growth’ scenario, we can assume Pudong’s urban transformation will push on in dramatic and partially organic fashion. Any adap- tion will therefore need to be based on clear principles and planning concepts that guide its ongoing urban evolution.

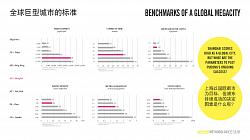

PARAMETERS

The sphere of influence of Pudong reaches far beyond Shanghai, and even the YRD. That makes de- termining the benchmarks for its future layout and its sustainability challenging. Comparing Shanghai’s density, congestion or green space to similar sized global cities is only superficially interesting. With the region Pudong’s success has relied largely on its ability to process large flows of people and prod- ucts from its ports, and efficiently transfer them to the rest of the country. This emphasis on logistic has shaped a landscape of dense infrastructural networks. However, in order to sustain its competitiveness other urban qualities will quickly need to gain prominence. An integration of comfortable living areas and diverse working and commercial areas will be crucial to establish Pudong as a competitive city in its own right. The question is, with space in short supply, which benchmarks should be applied to determine the effectiveness of one strategy over another.

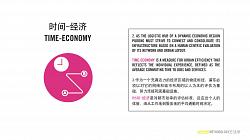

TIME-economy and SPACE-economy offer two unambiguous planning benchmarks that help evaluate planning decisions against spatial and temporal efficiency respectively. TIME-economy offers an lens to assess the efficiency of the urban layout, gauged as average commuting time. While, SPACE-economy evaluates land-use by comparing average public space versus private space in an area. They offer a more human-centric lens on ecocity planning by means of reflecting the experience of residents. Priori- tizing space and time means prioritizing planning.

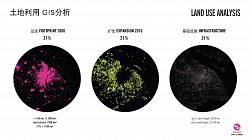

LAND=RESOURCE

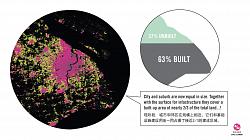

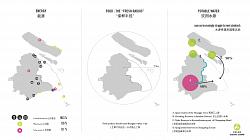

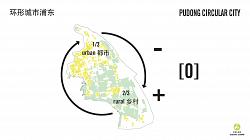

Our GIS analysis of Pudong reveals an extreme land use. We’ve traced built-up areas for a 60KM radius around Shanghai. The urban core (footprint in 2000), the suburban development (expansions between 2000-2010), and infrastructure each make up over 1/5 of the total land. This leaves 37% as open space — much of which cannot be classified as either productive land or natural ecology. Pudong Circular City carefully manages land-use and resource flows in order to reach a balance between urban consumption and rural production. Beyond the built-up footprint, we’ve analyzed the “Urban Fingerprint”, which com- pares the proportions of Pudong’s functional mix.

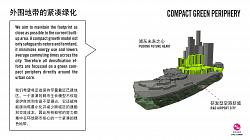

COMPACT GREEN PERIPHERY

Pudong’s urban program is not spread evenly. A strong central core and a steep density curve still char- acterize its configuration. The urban concentration this indicates is a unique advantage Pudong can take advantage of, as urban dispersion by planned and informal developments are generating increas- ingly fragmented urban patterns. We propose to rigorously apply a compact city model to the layout of Pudong. This should prevent the remaining non-urban space from ongoing encroachment and further fragmentation. This relies on maintaining the center of urban gravity as close as possible to the current built-up area. A compact growth model safeguards nature and farmland, minimizes energy use and low- ers average commuting times across the city. Densification efforts are focussed on a green compact periphery directly around the urban core. Public transit options and commuting times for the region as well as within Pudong support this concept. Measured from Lujiazui, the densest urbanized areas fall within an one hour commuting time reaching Huinan and Pudong Airport. These areas also provide the fastest access to Shanghai and the whole YRD.

TIME-economy, SPACE-economy, Urban Fingerprint and the density profile together allow us to formu- late a comprehensive spatial strategy that optimizes urban program, land use and urban form, in relation to infrastructure. This is the basis for a sustainable layout.

RESOURCE-ECONOMY

Having defined these spatial benchmarks, resilience and urban metabolism are charted. The metabo- lism of cities such as Shanghai or the Randstad that rely heavily on global exchange is impossible to observe in isolation. Equally their metabolism is impossible to make fully internalized. Instead, we strive to make nutrient, water, material, waste, energy and other resource flows as localized as possible. RE- SOURCE-economy aims to optimize these flows in order to make Pudong into a Circular City.

INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON

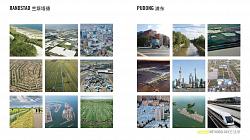

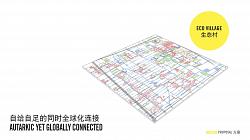

Pudong and the Randstad — the ring of cities that make up the metropolitan part of the Netherlands — have many spatial features, challenges and potential solutions in common. Dense and highly dynamic they both struggle to maintain an efficient yet livable rural-urban layout. In short their shared objectives can be understood as: a precarious spatial balance that seeks to support the largest harbor and airport in their respective regions, allows growth of the urban economic centers, and preservers the unique wa- ter permeated rural geography.

Pivotal for Holland’s 2040 Strategic vision is the protection and improvement of its “GREEN HEART” — the distinctive rural landscape at the center of the Randstad. This serves as our so-called green lung, a pastoral region that offers leisure and green space within arms reach of the urban centers, and acts as a sponge in a sophisticated integrated water management system that protects Holland’s flood prone landscape.

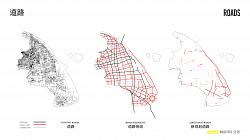

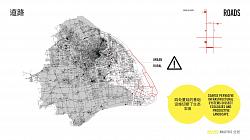

As airport and seaport in both regions expand, inland connections over rail and road become of criti- cal importance. In the Randstad rail has long-since been the backbone of the urban system providing fast transit between urban centers. More recently high speed rail starting at Schiphol Airport connects passengers swiftly to the rest of Europe. To keep the harbor competitive dedicated freight train lines connect Rotterdam to Germany’s industrial heartland. This vital logistic role the Randstad has played within the EU has produced one of the densest road networks in the world. However, this was achieved with a minimal impact on surrounding natural and urban landscapes. Specifically a clear hierarchy in the road network has resulted in a robust system. Bundling infrastructure created less propensity for roads to draw out suburban sprawl, or for tracks to slice natural ecologies. Comparing the road networks of the Randstad and Pudong reveals this quality. In Holland roads come together in compact corridors be- tween the urban centers, rather than covering large areas in a uniform grid. Street density in Dutch cities is 6 times that of Pudong, while rural road density is only half compared to Pudong.

II. SPATIAL ANALYSIS 空间分析

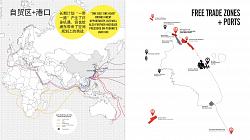

• PORTS / FREE TRADE ZONES 港口/自贸区

• ROAD SYSTEM 路网系统

• NATURAL SYSTEM 自然系统

• CORE PROGRAM 核心项目

• FUNCTIONAL ZONES 功能性区

• PROJECT SITES 项目场地

ANALYSIS

Nestled against the seaboard Pudong’s impressive logistic capacity has transformed large parts of the coastline into industrial zones. Many new efforts, however, are currently in play that aim to reclaim the coastline as natural landscape. As we see in the Netherlands, a natural beachfront is not only important for successful tourism and a rich biodiversity, it is fact the first line of defense against floods and rising tides.

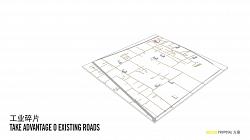

The Dutch dunes and the fine network of waterways behind them form an integral system that is very similar to Pudong’s capillary network of canals and waterways. However, in Pudong excessive roads intersect these water systems and threaten to diminish their flow capacity. We’ve discerned which roads could be considered obsolete.

PROGRAM

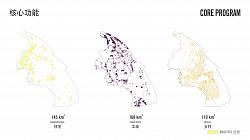

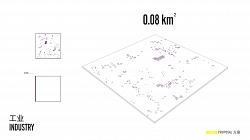

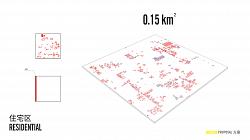

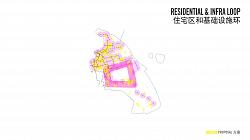

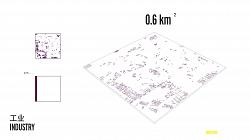

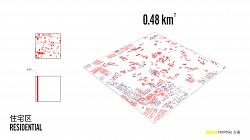

Beyond Pudong International Airport, Lujiazui, Disney and Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park as specialized nodes, we understand the general functional composition of Pudong as consisting of three elements: Residential (145km2), Industry (168km2) and productive rural land (110km2). These are the programs we aim to revitalize and streamline through spatial planning. The GIS maps convincingly indicate three trends: the emergence of a large courtyard-like residential loop, an increasingly fragmented industrial complex and a densely developed scattered countryside.

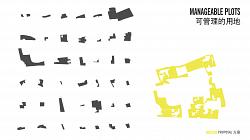

In the proposed strategy minimizing urban fragmentation is a central objective. However, the regional planning framework that exists is largely disconnected from how individual projects in Pudong are delin- eated. This disconnect makes combating fragmentation difficult. Project sites indiscriminately cut func- tional areas and intersect with ecological systems. Instead, in order to foster integration we have traced the main contiguous functional regions as our discrete planning areas. Each site comprises of one func- tion, or functional group — urban core, suburban ring, green heart, and logistic hub. These functional regions correspond with the four parts of the overall strategy:

A. Upcycling Downtown: Liberating the Block

B. Rural Remediation: The Taobao Village Module C. Urban Growth Boundary: The Water City Module D. Land-Air-Sea Hub: Pudong Airport City

PROPOSALS

A. UPCYCLING DOWNTOWN

LIBERATING THE BLOCK

• Slow traffic connections to Puxi

• Mixing up the block

• Opening up the compound

B. RURAL REMEDIATION

THE TAOBAO VILLAGE MODULE

改造城市城市 > 释放街区

Light-rail and living bridges

乡村整治

淘宝村模式 B1. Water systems as the backbone of a healthy and resilient productive landscape

• B2. Template for sustainable rural development

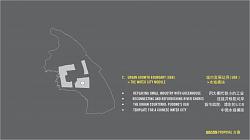

C. URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARY (UGB) > THE WATER CITY MODULE

• Replacing small industry with greenhouse

• Reconnecting and refurbishing river shores

• The Urban Courtyard: Pudong’s UGB •

• Template for a Chinese Water City

D. LAND-AIR-SEA HUB

PUDONG AIRPORT CIT

A.

• • • •

UPCYCLING DOWNTOWN

LIBERATING THE BLOCK

SLOW TRAFFIC CONNECTIONS TO PUXI MIXING UP THE BLOCK

OPENING UP THE COMPOUND LIGHT-RAIL AND LIVING BRIDGES

改造城市中心 > 释放街区

连接浦西慢交通

混合城区

开放街区

轻轨和生活桥梁

PROPOSALS

A. Upcycling Downtown

In recent decades numerous new bridges and tunnels have been built to travers the wide Huangpu Riv- er. For cars these projects of dazzling scale provide reasonable connections between the two shores, but they remain virtually inaccessible to bikes and pedestrians.

Connecting Pudong to Puxi, is not merely a matter of convenience, but is one of the pillars of its success. After the subway stops running in the evening visitors to Lujiazui are often stranded. This makes the area unappealing in the evening and hampers a transition to a more diverse commercial area that thrives on leisure, tourism and entertainment. We propose green slow traffic corridors that intersect downtown Pudong and then extend across the Huangpu River. Bike and scooter lanes and running tracks are built in the spaces underneath existing bridges, viaducts and fly-overs. This new traffic layer floats above the public parks and is covered from the rain by the road deck above. As we see in Puxi this space can also be used for BRT stations, which further integrates the pedestrians in the network. This proposal will be an integral part of the expansive waterfront rehabilitation effort and the ongoing refinement of the system of footbridges that have revitalized Lujiazui in recent years.

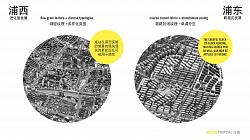

LAYERED FABRIC

Even a simple visual comparison between Puxi and Pudong reveals the unique contrast between their respective urban fabrics. The reality is that the historical morphology of Puxi is exceptional compared against other world cities. Although remarkably dense, its texture is intricate, layered and generally of a human scale. Its complexity is of a different order than Pudong, as it has been able to mature and adapt to countless of iterations of change over time. Conversely, downtown Pudong was laid out and built from a single vision and blueprint in single generation. The prevalent ideology at the time was geared towards separating urban functions within large city blocks intersected by a road grid of 6 to 12 lane inner-city highways. Within these quadrants a handful of developers took charge building countless repetitive residential towers without many supporting facilities.

This accelerated approached was successful in creating the iconic Central Business District and a vast landscape of hyper compact housing real-estate. The specialized housing typology of this era we’ve named the Pudong Slab. It is a hybrid between a residential high-rise and a slab tower, in the West more commonly used for social housing. With this extreme efficiency Pudong has realized its most valuable resource: a large mobile labour market.

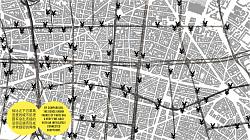

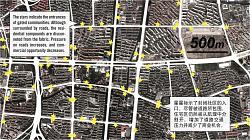

However, the requirements of Pudong’s urban population are quickly diversifying and the need for more livable and less uniform neighborhoods is becoming urgent. Yet, both the layout and fabric of Pudong will not be easily transformed to support this. Unlike the fine-grained texture and diverse typologies typical of Puxi, new planning guidelines resulted in monotonous functional zoning and a coarse texture of fenced off urban blocks. In many ways Pudong exemplifies the drawbacks of the cellular urban structure that is encoded in modern planning regulations. Compared to the fabric of historic Paris at the same scale, the absence of a revenue stream from an entire retail network becomes apparent. And more immediate social and infrastructural concerns abound that have made this particular urban typology obsolete. As president Xi explains: “In principle, closed residential districts will no longer be constructed in our nation. Existing residential areas and closed compounds are to be gradually opened, in order to utilize the internal roads, solve the problems of traffic jams related to the urban layout, and promote economical land use. In addition setting up “narrow roads, densification of the urban road layout, and hierarchy of expressway, primary and secondary distribution roads gradually branching off into a reasonable road system.” As policies are being introduced to steer away from gated communities, we are left to consider how, on a practical level, existing projects can be made more porous and socially integrated.

LIBERATING THE BLOCK

Mostly built in the last 25 years, many compounds will require some form of upgrading by 2040. We propose to diversify the function of the residential tower blocks by deregulating their single usage, introducing sustainable façades, and opening and then connecting the compounds. By deregulating the guidelines for residential towers a gradual process of diversification should kick in. Initially small studios and home offices, and soon after a growing number of tech and new media companies start-ups — us- ing 3-D printing for rapid prototyping, etc. — could benefit from more small offices available downtown.

LIVING BRIDGES

We can anticipate self-driving cars, traffic management and other advancements will substantially free up road space. However, even when the walls of the compounds have come down, the barriers that the wide roads throw up across Pudong continue to impede a pedestrian friendly environment. Effective new connections will be needed.

We propose a steadily expanding elevated light-rail network, which expands to connect local neighbor- hoods, and offers swift transit to your nearest subway station. This transit network is closely aligned to our proposal for an elevated retail ring. Introducing retail to residential areas is vital not just in order to generate new revenue, but to create a socially vibrant backbone at the neighborhood scale. This green network steadily expands to safely connect compounds over the highways. The ground level is largely left open, the first floor contains enclosed shopping galleries, while the roof has a park deck with biking and running tracks, much like the High-line in New York.

B. RURAL REMEDIATION

A vast area of the rural countryside of Pudong is protected farmland. This productive landscape in the estuary of the Huangpu River is an established historic agrarian typology. Similar to the Dutch polder landscape, its topography consists of an elaborate network of canals and streams along which long rows of farmhouses have lined up. However, encroachment from different directions continues to threaten this unique man-made ecology. On the one hand this comes in the form of common urbanization. The metropolis continues to roll out new districts and more infrastructure, and scattered industrial compounds that bisect the intricate system of waterways. While on the other hand farming communities have prospered from their prerogative to build rural villas and workshops on their own premises. Extensive village-level upgrading and informal industrialization has forged profound transformations of the countryside.

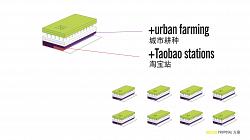

THE TAOBAO VILLAGE MODULE

In just a few years has the influence of e-commerce and mobile technology propelled industrialization of villages across the east coast of China and integrated them within the dominant urban economies. This has fuelled rural urbanization, but has also generated vital new sources of livelihood for struggling communities. We’ve set out to develop a rural planning module, that safeguards Pudong’s protected farmland from its intrinsic propensity to urbanize, while embracing the opportunities that arise from being part of the urban economy. The question is, can the countryside modernize without urbanizing further?

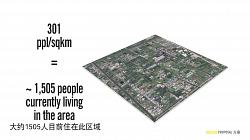

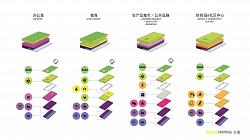

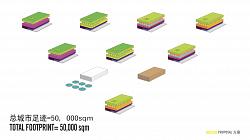

To develop the rural module, we have selected a 5 km2 rural plot for detailed spatial analysis. Agricultural and open land comprises three quarters of the total service area. Roads, waterways, facilities, farms, greenhouses and factories together make up a quarter of rural land use — half of which is built-up land, and occupied by approximately 1500 people.

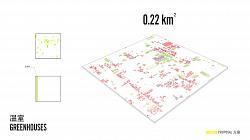

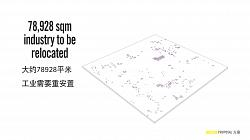

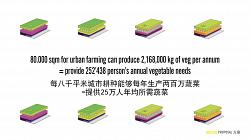

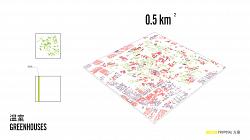

We’ve set out to preserve productive land against anticipated ongoing encroachment of all other urban program and infrastructure. The additional space that is required to offset the impromptu expansion is freed up by consolidating existing scattered industries. However, heavy concrete foundation plates — even under simple tin sheds — make make it expensive to convert these plots back to farmland. In our urban module (under proposal C), we will explore how larger industrial compounds can be compiled into a new R&D strip adjacent to the airport. For the rural context, however, we have investigated a process of remediation. Rural industry is small, scattered and informal, and also constructed on hard-to-demolish baseplates. We aim to reuse these foundations to construct modern greenhouses for intensive farming. The futuristic glass landscape of the Westland next to Rotterdam provides an intriguing reference.

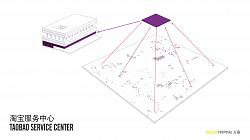

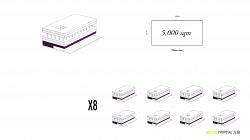

The industry itself is grouped and stacked to form new rural production centers, which are constructed exactly within the existing built-up footprint. The new production hubs combine industrial workshops with other facilities the countryside needs, and have through virtual technology come within reach. The six story hubs, or “Taobao Service Centers” represent an average of rural space requirements and can vary from location to location. Their program includes workshops, education, basic healthcare, urban farming, offices, sports and community center, and a Taobao Station. In addition, every rural module will contain two sustainability hubs; one biomass and one wastewater treatment plant. The greenhouses to- gether with the farming in the Service Hubs provide enough food to make each plot self-sufficient. This makes the Taobao Village typology the cornerstone of urban sustainability. Virtual technology elevates rural lifestyles to that of the city, while increased efficiency through stacking of functions and intensive indoor farming allows Pudong to preserve its farmland.

PLANNING WITH NATURE

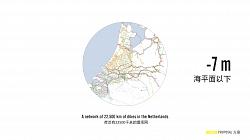

Two-thirds of the world’s cities are faced with one or more water-related threats — rising sea levels, flooding rivers, inundation, dropping water tables, polluted sources, drought. These problems are often intricately related. With global warming taking hold we can expect the challenges will only augment. As Europe’s main estuary, Holland presents one of the earliest examples. Even a big city such as Rotterdam is up to 7 meters below sea level. To keep the water at bay a comprehensive network of dikes and levies has been put in place. In Holland this centuries-long effort is as much part of the landscape as it in our cultural DNA. As such, water and water management infrastructure is carefully embedded at every scale, both physically and politically. This is an important distinction from the heavy-handed application of water infrastructure that is increasingly prevalent, particularly across Asia. Entire island cities are being planned as part of extensive coastal protection schemes — a strategy which in some ways correlates to our proposal for AIRPORT CITY (Proposal D). However, for the fine water networks of Pudong’s protected landscape much more subtle tactics will be required.

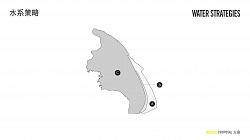

In recent years an opposite trend has been developing that understands rivers and coastlines as dynamic systems, and that benefit from a soft ‘refurbishing’ over hard control — Linggang’s “sponge city” concept is in related to this approach. Tracing the edges of Pudong’s shoreline over time illustrates the continuously evolving nature of the coastal landscape. Flooding simulations for Shanghai at a global temperature increase of 1.5°C and 2°C reveal respectively serious and severe waterlogged conditions. Interestingly, they also indicate that much of the water will be related to inundation, rather than to direct flooding. This may explain why the heavily built-up areas in the urban core remain relatively dry. This puts increased emphasis on water management of the countryside, rather than merely of coastlines and rivers. This should explain, what otherwise may seem somewhat hypocritical for a Dutch company to advice against a model of heavy infrastructure to make Pudong resilient. As an initial thought model, we have opted to investigate a more cascaded set of tactics. We distinguish three zones: A. coastline refurbishment (and sponge city), B. staggered dikes, and C. riverscape amelioration.

A. Coastline refurbishment builds on the ongoing efforts of enhancing the natural ecologies and dune landscapes as a first line of defense. This part of the strategy encourages Linggang to develop into a truly progressive and sustainable sponge city.

B. Adjacent to the dunes of Linggang a natural formation of three parallel rivers offers a logical

opportunity to introduce harder edge. Along the east side of each river a higher dike doubles — that can double as a road — creates a naturally staggered defense line.

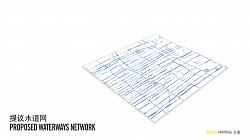

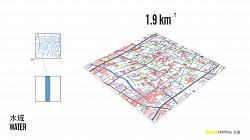

C. Pudong’s capillary waterways closely resemble the Dutch polder, and as such should be con- sidered an integral part of holistic water management. Their proper functioning relies on an uninterrupted drainage of rain and groundwater. As a first step we propose to heal and connect any dead ends in the water system. Secondly, we make the riverbeds permeable and accessible for recreation. Importantly, we aim to prevent obstructions of the natural water flows, or incursion of the water table by large build- ing blocks constructed directly on riverbeds. The layout of the Water City module (proposal C) illustrates how a city can be planned without altering the structure of existing waterways.

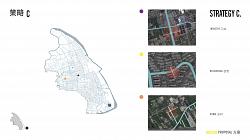

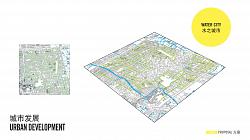

C. URBAN GROWTH BOUNDARY

GROWTH SCENARIOS

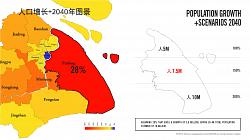

When planning the main urban layout for Pudong 2040 anticipating the population growth is of crucial importance. However, making reasonable projections is difficult in a region that in recent decades has changed its social, economic and spatial landscape so profoundly. Therefore, we’ve opted to investigate three different growth scenarios: low (100%), medium (150%), high (200%).

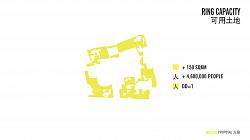

In the low growth scenario, the current population of just over 5 million people will remain constant. More likely, however, is a medium growth scenario, for which planning should be able to accommodate 7.5 million inhabitants. Finally, considering Pudong is the region’s fastest growing district (30%), we have also investigated a high growth rate, that would double the current population, which should result in a masterplan able to support a population of 10 million permanent residents.

Important, however, is to anticipate that under any scenario the total urban footprint will continue to in- crease (due to new public and commercial facilities, infrastructure and higher average living space per capita, a large transient community, etc.). Secondly, we believe it is reasonable to assume that despite population growth, average densities will remain the same. This has been true for the YRD at large over the last decade, and can be contributed to compact typologies such as the Pudong Slab, which maxi- mizes land use. This unique condition simplifies the application of scenario-based planning, as it means that — against the trend of most expanding cities — population density remains constant over time. The index we developed to chart this is Dynamic Density (DD), or the change in ratio of a area’s average population density to its urban footprint. In short, for the three scenarios we are assuming DD = 1. This gives us three required surface areas. These are compared to the mappings of the current built-up area, which reveals additionally required urban land.

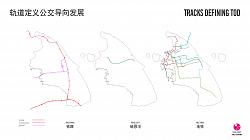

Following the logic of transit oriented development (TOD), all future growth should happen within a rea- sonable 2 km (5 min) biking distance from a subway station. This delivers an envelope that limits and strictly defines the potential expansion. However, there where stations are realized outside of urban ar- eas, this logic also allows some unurbanized land to be designated for expansions.

THE URBAN COURTYARD

The current urbanization pattern reveals the formation of a large triangular loop. Beyond the CBD and Zhangjiang Pudong’s development seems to have extended along a U-shape, following roads and ex- isting settlements, with the airport applying a strong gravitational pull. This has created an agricultural heart surrounded by city, comparable to the Green Heart in the Randstad, or what we’ve coined as Pudong’s Urban Courtyard.

Although in dynamic metropolitan regions we should be skeptical of the effectiveness of a so-called a ‘urban growth boundary’ (UGB), the unique layout of Pudong’s Urban Courtyard makes it feasible as an growth boundary.

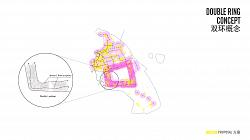

This provides us with a starting point to guide Pudong’s ongoing expansion within a clear spatial frame- work that corresponds with the intrinsic direction of growth. For each of the 3 scenarios our proposal is to strengthen the Urban Courtyard and apply it as a structuring element. For the first growth scenario the borders of the ring are traced and aligned with strong geographical features such as rivers and high- ways in order to establish hard edges. Then green corridors (gates) are cut out of the courtyard walls that connect the green heart with the rural areas outside of the ring. During the second scenario, small urban expansions can occur within the 2 KM radius of existing stations. In the third scenario this is ex- tended to any new metro stations completing the full courtyard.

An important advantage of the Urban Courtyard is that it functions as a public transit loop. This circular system is optimized by extending all isolated end stations with lines that connect back into the metro net- work. This is a technically cost-effective way to improve connectivity, moreover, it improves commutes between local communities, rather than merely to the city center. This strategy includes extending metro line 18 to the new high-speed rail (HSR) station next to the airport. This achieves a new transit backbone for the Urban Courtyard, with parallel lines all along its perimeter. Especially for residents living on the remote south side of the ring this greatly enhances overall accessibility.

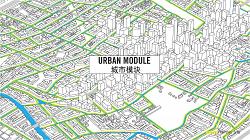

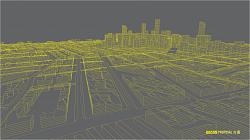

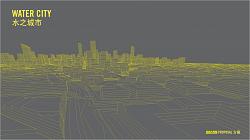

THE WATER CITY MODULE

Up to five locations within the Urban Courtyard can be developed without impeding on the Urban Growth Boundary. This create urban space for if Pudong evolves into the third, high population growth scenario. Urbanizing these plots in a sustainable fashion can reinforce the functionality of the Urban Courtyard. The question is, can we plan new cityscape without impacting the intricate waterways of rural Pudong?

Historically towns and villages in the region have been planned with extreme care to adhere to the unique hydrology of the area and cherish its natural resources. Several ancient water towns still exist in Pudong today. However, this wisdom has been trumped at every scale, from regional highways, to city-level zoning, to the local street grid and the layout of residential compounds, by regulations and commercial interests that ignore the more subtle aspects of natural ecologies. The challenge we faced while designing a module for a contemporary water town was the density and scale that urban projects in Pudong require. As we prepare to fill in the remaining plots of the Urban Courtyard, we are not so much designing a modern water town, but a WATER CITY.

As for the rural module, detailed mapping of the current topography and land use are essential first steps. Water, forest, historic sites and villages are preserved. Dead-ends in the water bodies are connected to the network, which becomes the base layer for the master plan. So rather than projecting an urban pattern on top of the rural context, the layout of roads and buildings adapts precisely to the land- scape. Like the canals of Amsterdam, the rivers and streams become the spatial framework of the new city along which all activity takes place.

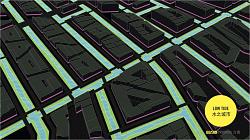

The water level in these streams is allowed to fluctuate with the changing seasons. Within the embankments of the entire network a flood plane is incorporated. With lower water levels, a green strip of water-filtering reed beds is revealed, that doubles as an ideal recreational space. Interspersed throughout the Water City are parks of different sizes and characteristics. Only two main access roads intersect the Water City. Where they cross a center forms. But also along the subway stations building densities intensify. The residential areas around the center are planned with a perimeter block typology. Their flexible layout adapts well to the meandering pattern of rivers. Although just 6 stories, their compact layout offers densities comparable to the compounds of Lujiazui.

The highest floors are stepped creating large terraces that can be used for private recreation, but equally for urban farming or for placing PV-cells. The entire ground floor is commercial, which generates long strips of uninterrupted storefront. The blocks are porous and the internal space is semi-public. In addition, about one in four of the perimeter blocks is broken up in parts, that wrap around a plaza. This turns the block inside out to create large retail spaces, or intimate city squares.

DOUBLE LOOP

To capitalize on the union of air and land-side, Pudong Airport will need to be connected with a near seamless high-capacity transit link. We have conceived Pudong Airport City as developing around a double mono-rail loop that efficiently connects the new harbor and sea terminals to the airport terminals, to the subway and the new HSR stations. This driverless system swiftly connects the large labor force living in Pudong to employment opportunities generated by PUDONG AIRPORT CITY.

D. PUDONG AIRPORT CITY

Aerotropolis

The ubiquity of jet travel, round-the-clock workdays, overnight shipping, global business networks and urban congestion have aggressively pulled urbanization towards distant airports. Increasingly this unique form of suburban expansion is generating secondary urban centers emanating substantial urban gravity. In response to this trend, cities from Amsterdam to Beijing have embraced airport urbanization as a model to develop new real-estate and land-side businesses as a means to supplement airport operations with non-aeronautical revenue streams. For many airports this amounts to 40–60% of total revenue (Global Airport Cities, John Kasarda). This economic potential has ballooned the mega-airport into an urban-logistic hub, or aerotropolis: a city centered around an airport, complete with an ecology of business, leisure, logistic and production facilities.

As urban economies become globalized the speed and range of air travel and air freight offer competitive advantage. In the aerotropolis model, time and cost of connectivity replace space and distance as the primary metrics shaping development, with “economies of speed” becoming as salient for competitiveness as economies of scale and economies of scope*. In this model, Pico Iyer argues, it is not how far, but how fast distant firms and places can connect. To be able to travel quickly to Amsterdam or Shanghai can be more important for business than to be close to the city center. Marx’s prophecy of “the annihilation of space by time” continues to unfold.

The aerotropolis has absorbed metropolitan convenience and culture. Distant travelers and locals alike can conduct business, exchange knowledge, shop, eat, sleep, and be entertained without going more than 15 minutes from the airport. This makes them both powerful engines of international trade, as well as engines of local economic growth, attracting a range of (loosely) aviation-related businesses. The economic opportunities are profound — an airport such as Dallas-Fort Worth employs 400,000 jobs within an 8 km radius. For many companies, their staff and their clients airport cities have become the center, and the city just a distant suburbia.

PLANNING PUDONG AIRPORT

The aerotropolis as the beacon of the global city, brings possibilities as well as many pitfalls. Amsterdam Schiphol Airport was an early adopter of the Airport city model and still serves as an important example of a carefully planned aerotropolis. However, many airport cities are much bigger and have developed along different paths, evolving largely organically, fuelled by different drivers of urbanization:

(1) land availability

(2) improved surface transportation,

(3) growing air travel demands

(4) airport revenue opportunities

(5) new business practices

(6) attraction of business and real-estate development

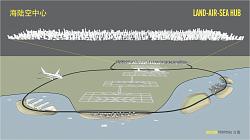

Regardless of the process, airports continue to transform from primarily air transport infrastructure to multimodal, multifunctional nodes generating considerable commercial growth well beyond their boundaries. This holds particularly true for Pudong Airport, as it embraces a new future, with new runways and terminals, that are part of a number of ambitions plans, including a new high-speed train station, extension of the Maglev, and a new sea port. This will make Pudong among the largest and most diverse land-air-sea hubs in the world.

Invariably, urbanization of the land directly surrounding Pudong Airport, but also of the district of Pudong as a whole, will accelerate. To fully utilize the economic, employment and logistic opportunities of these projects, while mediating their environmental impact, these expansions must be coordinated within an overarching plan for Pudong Airport as a new aerotropolis, or simply as: PUDONG AIRPORT CITY.

AIR&D CITY

Land close to flight paths is not suitable for residential program, nature and the birds it attracts, is equally unsuitable, as they pose a risk to airplanes. However, the transitional zone that is required presents an opportunity. The strategic proximity of Pudong Airport flanked by our proposed plan for Pudong Urban Courtyard suggest an altogether new spatial configuration can be achieved: an airport city, where its two main components (logistic hub and urban center) will not obstruct or choke each other as they develop.

We’ve conceived a mixed-use strip that is functionally part of both the Urban Courtyard and of the air- port, and branded this part of Pudong Airport City as “AIR&D City”. Its layout is based on a modular system of irregular quadrants in a network of 10 x 2 km. AIR&D CITY is concentrated around the new high speed rail station, and connected to the the new harbor, supporting a broad mix of business and industry. Located in between city and airport the strip functions as a buffer. Here the noise-intensive industries that currently are scattered over Pudong can be relocated. Industries merge with airport re- lated business, including time-sensitive manufacturing and distribution facilities, hotels, entertainment, retail, convention, trade and exhibition complexes, and office buildings. Because city and airport-related functions supplement each other, over time an integrated technology and innovation hub begins to take shape. In turn, the advanced production facilities attract research and educational program in the form of university satellite campuses and R&D of international companies.

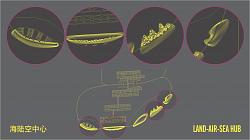

AND-AIR-SEA HUB (LASH)

Pudong Airport has been expanding deeper into this sea. This brings an ambitious proposal to integrate the airport with a comprehensive sea hub a step closer. In particular freight and tourism could benefit from a new multimodal transit complex. However, any additional expansion into the sea has to be conceived with careful consideration for the natural environment, such as dune landscapes, but also sea currents and shifting sand banks. Much of this data is currently still absent and will need to be collected and analyzed in ensuing stages. However, we feel within the larger vision for Pudong 2040, a spatial proposal for Pudong as a multimodal hub is important and can provide a framework for a detailed feasibility study.

The new airport harbor will consist of four components: a deep sea container harbor, passenger and ferry terminals, cruise terminal, and a marina. Central to the planning of this sea hub is the construction of the new runway on reclaimed land. This has created a large triangular protrusion into the sea. Our plan for Pudong Sea Hub makes use of this protrusion as an ideal mooring site for large cruise ships. Planned as the only terminal located on the mainland, cruise passengers gain direct access to the airport terminals. The challenge will be to allocate space for the other entities, without expanding further into the ocean. To solve this, port, ferry terminals and marina are each located on dedicated islands that are draped neatly in the lee of the coast, or the armpit created by the new runway peninsula. This careful positioning on different islands softens its hydrological impact and aims to maintain the natural water flows along the coastline. This creates an inner bay with calm water for smaller boats, and and outer bay, easily accessibly from the seaside. As larger cruise and cargo ships do not need to enter the inner bay, the bridges that connecting the different islands and the mainland with a monorail, can be designed to have minimal impact.

One island remains undeveloped. It is planned for water recreation and will be home to a new beach for Pudong. However, this is not merely luxury. This ring of islands is the final component of our comprehensive water management and urban resilience strategy. Although part of a vast infrastructure investment, it represents an alternative to building heavy dikes to protect the airport. Instead, like the sponge city concept applied all along the cost, the islands work with nature in a dynamic way, dampening the tides waves and applying the currents to keep the coastline strong. Resilience, recreation, mobility is all achieved holistically by forming an alliance with nature. If there is anything we can learn from the Dutch method, this would be it.

TEAM

Neville Mars

Liu Chang

Mark Biemans Chiara Luisa Ferrario Cedric Van Parys

Li zi Xuan

Lu Xuan

Emma Zhu

Luke Cardew

Owned by / Added by neville mars / 17.0 years ago / 126455 hits / 11 hours view time

Tags

Latest Entries

Contribute

Login to post an entry to this node.