GBD

DCF proposal for GBD sustainable Art + Design District

Client BOLONI Kebao

Team DCF: Neville Mars, Jeanne - 边静, Brice Bignami , Wang Zi

GBD 500 M3 design competition; visit the application website

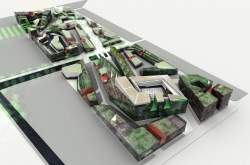

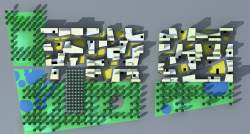

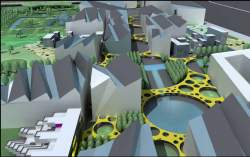

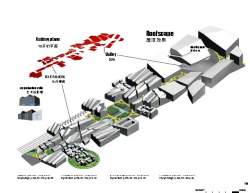

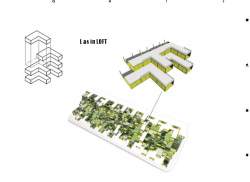

3D sketch of 500 M3 site and south area in Google Earth (preview above)

Phase 2-3 South area plans: GBD Green Wall PDF (5 MB).

Below the previous versions and background texts for the GBD Art + Design District:

concept proposal 2: In collaboration with Wenjing Huang of O.P.E.N. Architecture Studio

Download the diagrams for Chapter 2 - The cell-pattern concept - GBD poster!

Gao Bei Dian art+design district / design 1

Team DCF design 1:

Neville Mars, Saskia Vendel, Li xin Lu - 李心路, Vicky Wang - 王颖, Yaxin Liu - 李亚鑫, Naihan Li - 李鼐含

Beijing is not only the capital of China; it is the cultural heart of the nation. Today it offers a unique mix of a vast historic heritage and a progressive and thriving art scene. The influx of foreign visitors and an ever-increasing number of young successful Chinese has generated a demand for retail and leisure of international standards. This is a new market looking for style, comfort and culture. Gao Bei Dian (GBD) is a fast developing antiques and leisure district at a ten minutes drive from Beijing’s central business district (CBD). The mission statement for the Gao Bei Dian Art and Design District is to create a sustainable park where the rich flavors of Beijing’s art community are combined with top quality retail living and leisure space.

Event Garden

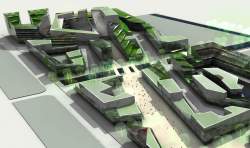

This unique combination of ingredients nurtures and supports itself. It offers a well-facilitated living environment for its residents and a rich and diverse shopping and leisure environment for visitors. The streetscape changes from large and open to small and intimate. Indoor and outdoor spaces are thread together to form a continuous yet constantly different experience. Ultimately the streets, the squares, the water, the park and all the buildings work together to become one public space specifically designed to accommodate large events. This is the GBD Event Garden.

Backbone

Artist communities are a big success and developing fast in Beijing. Anything from villages to factories is converted for the creation of art. They are by nature diverse and growing spontaneously. The challenge for the urban plan of the GBD Art and Design District is to allow the three central elements – sustainable park, commercial strip and art village – to develop naturally and gradually yet as one integrated system. Quintessential to the project is an urban backbone that forms the basis for a flexible yet highly efficient district. This gives artists the freedom to contribute personally to their own studios and surroundings and capture the real bohemian quality of Beijng’s art scene. At the same time this backbone allows the commercial program to gradually develop to achieve its full potential.

Download booklet new area Full PDF or GBD slide presentation

GBD

北京不仅仅是中国的首都,还是文化的中心。如今他带给我们的是一个别具一格的融合了大量历史遗迹和进步的繁荣的艺术景观。大量外国游客的涌入,和持续增长的年轻的中国成功人士都说明了对国际化零售及休闲标准的需求。这是一个寻求新的格调,安逸,及文化的市场。 高碑店(GBD)是一个发展迅速的古韵休闲的地区,距离北京的中央商务区(CBD)只有十分钟的车程。关于高碑店艺术及设计区任务的说明就是创造一个融合丰富的北京艺术区情调和顶级消费,休闲居住空间的持续性园林。

活动园

这是一个结合了原有的自然环境并且维持自身发展的园林。他带给居住者的是一个设施完备的居住环境,带给游客的是一个丰富多样的购物休闲环境。街道的范围由开阔到狭小再到私密。户内户外的空间贯穿在一起形成了一个连续不断的不同的感受。最终街道,广场,水,园林和所有的建筑相互作用形成了一个专为大型活动设计的公共空间。这就是高碑店活动园。主干-发展自由 艺术村在北京取得了巨大的成功且发展迅速。任何从村到工厂的东西都演变成了艺术的创造物。他们的性质多样,自然发展。GBD艺术设计区的城市计划的挑战在于要实现三个关键因素- 持续性园林,商业街区,艺术家村—自然稳步的整体发展。该项目的实质是一个城市的主干在灵活发展的基础下形成的高效艺术区。 这带给艺术家致力于他们个人工作室及周围环境的自由,在北京的艺术景观中抓住真正的漂泊本质。同时,这条主干可以商业活动逐渐发展便且实现其所有的潜质。

Concept

Our premise when making urban proposals in China is to cross-connect the urban

network; defining a public realm that results in an exciting and diverse street life when most real-estate projects are turned away from the public domain. This means connecting streets and avoiding dead-ends. The reality of the Beijing suburbs however has left us looking for loose ends to connect. Though only a few minutes away from Beijing’s CBD and blessed with a developer keen on making an open and accessible district the project site near GBD along the East 5th Ring Road is isolated by its surroundings such as infrastructure and water.

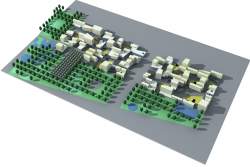

The combination of homes and art studios in the village has allowed us to orientate

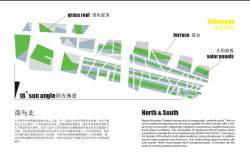

the urban design both to the south and to the north at the same time. This has become the basis for environmentally sustainability. The compact and integrated scheme of the urban strip frees up maximum green space; the entire south part of the site is now available for an advanced ecological park.

我们希望在中国城市方案的制定就是与城市的交通网交错相接;公共场所不再有房地产商,取而代之的是丰富活跃的街边生活。这就意味着要将所有的道路紧密连接,避免死路的出现。然而北京郊区的现状只能让我们寻找一些稀少的死路来连接。这个项目的地理位置在距东五环不远的高碑店附近,并且完全与周围环境相隔离。尽管它距离北京的CBD只有几分钟的路程,同时也寄予了开发商再此建立一个方便到达的开放社区的渴望,但是以高速路为界就如同那些封闭的社区一样从周围的环境中隔离出来。

在商业区中所有的建筑都是环绕着狭长路段上隆起的一座小山而建的,因此在中心位置就出现了一个巨大的户外剧场,而且那些屋顶也都向着舞台的位置倾斜。村庄与园林的交汇处便是户外博物馆的所在之处。村中家与工作室的结合使我们可以让城市设计同时面向南北两个方向。这里还是环境的持续性基地。狭长的城市路段紧密划一的方案设计释放出了最大的绿色空间;因此整个南部地区可以用于建设一个先进的生态园。

Ecological Event Park -- 生态活动园

Chinese residential and park design projects tend to be very straightforward. Their appearance is limited to a few basic prototypes. In Beijing the art village too is becoming a standard prototype. All three areas are most likely to be found in the suburb. Their integration projected on this chaotic context requires a new aproach.

中国的住宅和园林设计项目倾向直观化。它们的外观仅限于几种基本雏形。在北京,艺术村同样也变得逐渐形成了一个标准的模式。现有的三个地区都是在城市郊区建立起来的。这使他们理想即使不必要的项目都在清晰浓绿的目的下发展。

China is on the verge of a green revolution. The Chinese government is looking for new ways to introduce sustainable technologies into the built environment. The Gao Bei Dian Team is at the forefront of this process with the creation of a beautiful, educational and exciting sustainable park that supports and gives life to the entire district. The most innovative thinking and the latest technologies are working together to make GBD the greenest urban project in Beijing. Green buildings, passive and active solar power, wind energy, no soil export, space efficiency, recycling, a park of plant and wildlife indigenous to Beijing, minimum hard surface and most importantly a comprehensive water purification and management plan make Green GBD a example project for China’s future. The design and materials result in healthier indoor air and more natural light. A building integrated solar system supplies 5% of the electricity. It has an on-site black water system to eliminate the use of potable water for the building’s flush system and supply the heating, ventilation and air conditioning cooling tower. It also contains a storm water catchment system to irrigate the rooftop garden.

中国正处在绿色节能环保革命的边缘上。中国政府也在努力寻求可以将可持续性的技术融合到建筑环境中的方法。高碑店工作组就是在寻求创在一个漂亮的,有教育意义的,令人振奋的可持续性园林过程的前沿,这个园林会支撑并且给整个地区带来活力。

最具创意的想法与最新的技术结合共同使高碑店成为北京最绿,最节能的城市项目。节能的建筑,有源与无源的太阳能源,空间的有效利用,再循环,又自然生长的植物与野生动物的园林,最少的道路面积,最重要的是覆盖全区的水过滤系统和使高碑店成为中国未来发展的一个实验性项目的计划。

这样的设计和材料可以带来更健康的室内空气和个自然的光线。一个带有太阳能系统的建筑可以为其自身提供5%的电量。他本身还带有一个黑水系统用来避免将饮用水用于抽水系统,供暖,换气及冷却塔。同时这里还有雨水收集系统用来浇灌屋顶上的花园。

INTERVIEW: Pondering the Green Edge*

Erich Schienke talks with Neville Mars

ES: What were the issues concerning you when you started the designs for the L-building and for the GBD Art and Design District?

NM: As a foreign designer working in China pushing a progressive sustainable agenda is one of the few added values we have to offer. China’s impressive green ambitions for 2020 have produced an array of studies, suggestions and guidelines aimed at reducing emission levels. This is important, but the magnitude of China’s problems demands a more profoundly integrated approach. And China, as it will double its building stock over the next two decades, has this unique opportunity. At the outset of what is potentially a green revolution it is essential to aim for more then reducing the environmental impact with a myriad of greenification gimmicks. To achieve this, I believe efforts should include both ends of the scale, now largely ignored — the regional and the individual.

My concerns on the regional scale relate to the increasingly suburban landscape that is forming. We have coined the term splatter pattern* to describe the vast urban expansions taking place at village-level. Based on the premise that a significant proportion of future consumption is already determined once land use and urban form has been designated, this will constitute highly inefficient urban regions. The harsh reality China has to face is that even a collection of good green buildings can deliver a bad city. The anxious socio-economic context facilitates the almost instantaneous shift from a red to a green society — at least on paper. But coherence between the sea of new building projects is much more difficult to realize.

ES: What about individual level problems facing greening in China?

NM: About the problems at the individual scale I am less skeptical. A green society is not the product of laws and guidelines alone. The individual, or rather the consumer, will define the success of most green ambitions. Like so many aspects of China’s modernization it’s the combined result of top-down government interventions and bottom-up incentives that generate the hyper-speed transition. China’s double-digit economic growth can be argued to be at a standstill when the environmental squalor costs an estimated 10% GDP annually. At the same time air pollution is directly affecting the health of millions of individuals. According to the Chinese Academy on Environmental Planning (2003), air pollution is the cause of 411,000 premature deaths every year. This is particularly poignant when you consider that the average individual in China consumes only a fraction of what people in most Western countries do. We are faced with a rather paradoxical aim in terms of greenness: less to reduce individual consumption, but to serve and stimulate future green consumers.

Chinese society is in the process of a complete transformation. The objective is to accommodate the xiao kang* or well-off middle class in a new urban environment by 2020. This means we have to conceive what the urban environment should be now. Though cities like Beijing seem to be modern, in reality they are realized with just another upgrade of a monotonous housing stock. High-end green efforts are mostly aimed at prestigious office towers and tend to overlook the challenge of the explosive residential realm. In crude terms the housing program can be reduced to dormitory extrusions* and villa parks. As the Chinese home consumer diversifies this monotony will be disastrous for the lifespan of a notoriously short-lived housing-stock. Having completed a brand new* urban environment at the scale of Europe in two decades, China would have to start all over again, green buildings or not.

Ultimately the individual and regional scales affect each other. China has embarked on a social revolution that can be summarized as a shift from a single society of radical equality to a radically segregated society. The scattered urban landscape that is forming is defining the modern Chinese way of life. For those who can afford it, this equals a car-dependent suburban lifestyle. While mass-consumption is on the rise for some, dismal conditions remain for many. Greenification schemes are mostly up-market, simply pushing primitive conditions to the edge of society. The fact that China has ventured on a path that is not socially sustainable will hinder its ambitions for environmental sustainability.

ES: I agree that a massive transformation is underway, but within the context of Chinese history neither inequality nor difficulties of scale are in themselves new. Do you put the radical aspect of these changes down to speed and the numbers involved, or is there a fundamental morphological change happening? If the landscape is undergoing complete transformation, are traditional and even current forms being lost?

NM: Traditionally Chinese cities were compact clear centers in the landscape. Even during the twentieth century cities did not expand beyond the reach of the bicycle. The neighborhood was integrated; work and living were closely aligned. Though not sustainable in a modern society this presents an ideal configuration on both the scale of the region and the individual home. Even today for the 200 million households that don’t have running hot water, economizing on energy is painfully easy; more so for the 20,000 villages entirely cut off from the grid. Ironically the lack of the most basic amenities and infrastructure has accelerated the spread of sustainable technologies. China is the world's largest producer of solar panels, and the number of people still off the grid have made it the world’s largest consumer. In the countryside a staggering 50 million collectors have been installed. However leapfrog developments have uprooted the urban fabric on many levels. The compact city and the social setting of the traditional neighborhood are all but lost in the expansion of the Chinese suburb.

China’s hukou* registration system divides the population into two distinct groups: urban and rural. This suggests two distinct spatial conditions: the city and the countryside. However the predominant development occurs on the threshold of these two and produces nothing more than a rurban* landscape — an indiscriminate fusion of rural and urban elements that lacks the qualities of either condition. To gain a grip on the landscape at least three basic conditions should be distinguished: rural, urban and suburban. The suburbs and the suburbanite define the residential median of China’s expansion. It is the most dynamic zone, with potentially the largest impact on the environment. Here the values of the traditional neighborhood and the compact city should be reintroduced.

ES: And so the suburbs are the “Green Edge*” your designs refer to?

NM: Originally the title of our research, the Green Edge*, was a cynical reference to one part of Beijing’s greenification scheme: a project that has edged major roads, particularly around international tourist attractions, overpasses, and the international airport expressway, with a thin sleeve of trees, plants and flowerbeds. In a notoriously dry city, this seems to be a water-thirsty fauna offensive to make Beijing look green from a car, while blocking the view onto dilapidated neighborhoods around the Third Ring Road. But we felt this name was more appropriate for the zone around cities with the particular green potential we have distinguished in our urban proposals*. The objective for this zone was to define the edge of the city in order to tackle sprawl. It became clear in China that the suburb has to be given a second chance — if only because of its success.

At the moment the Chinese suburb is no more than an indiscriminate region where fortunate home-owners, the forcefully relocated, and ever more middle-class citizens are finding refuge. The trend itself is thoroughly global — people either want to live in the suburbs or can’t afford to live anywhere else. But here, for young real estate refugees*, the flight to the suburb is the Chinese Dream*. It too has its roots in an economic revival and the success of mass-consumption and individual transportation. But the Chinese suburb is still distinct from its American counterpart. The Chinese suburbs still contain real social diversity and a variety of spatial conditions. This may be only temporary though, as an unseemly form of over-planning* dominated by highways and industrial parks is pushing small-scale developments out to the periphery leaving behind a sterile and inaccessible landscape. Still I feel there is hope. Unlike American suburbia, the Chinese suburbs often present remarkably compact building typologies. This is a potentially invaluable condition that China should nurture to give quality to its urban periphery. Paradoxically urbanization, mass-migration and population growth can help to elevate the suburb to become an integrated part of a compact metropolitan environment.

To achieve this, suburbia should be confined to clear boundaries. Where suburbia starts and stops however is hard to define. We have suggested any urban expansion beyond the reach of high-end public transport should be considered unsustainable. The zone within the mass-transit system which is not part of the center we have coined the Green Edge*; a transitional zone between the city and the countryside. Freed from its derogatory appellation and its image as a refuge for rich and poor, this part of the suburb can take on the role of being the city’s green heart, accommodating a rich mix of social classes, densities, urban functions and green space. The Green Edge* introduces a highly sought after urban quality: lush residential environment with fast access to the center.

ES: But aren’t suburbs normally perceived to be at the heart of the sprawl problem, rather than the green solution?

NM: True — we are claiming green building projects belong in the suburbs of large cities — and we are aware that this statement is counterintuitive. China is currently in the grip of a satellite fetish*. Somehow with satellite towns suburbanization is not a concern. Building more satellites and celebrated concept towns should compensate for the inexorable expansion of China’s semi-industrial, semi-modern, semi-urban landscape: the satellite town has become the focus of an eco-exodus.

And in principle it can work. China, the world’s most sophisticated developing country has signed a contract to build the world’s first completely sustainable city near Shanghai. Engineered by Ove Arup & Partners and located on an island it should be a successful, truly autonomous green city. However, most likely the countless other green planning projects will be less comprehensive and less autonomous. They will induce sprawl and demand longer commutes instead of enhancing the semi-developed periphery. This is why green projects belong in the suburbs, or rather the Green Edge*.

The eco-exodus and the concept of a sustainable satellite are not new. They are reminiscent of the ideologies of New Urbanism (NU); a movement which proclaimed the invention of a socially refined, walkable eco-town of human proportion with historical trimmings back in the eighties. However as a socially environmentally sustainable vision NU and its offspring Smart Growth are impaired by their car-dependency and price tag. Their walkable qualities entail only the stroll from the house to the church and the barbershop. They lack the critical mass* necessary to support high-end transit to the workplace. In addition they build on what was previously open space. This reduces New Urbanism to a gated community without walls; the result of carpet planning* with stylistic cues. Its most prominent examples — Celebration, Seaside, and The Glen — are tantamount to a privatization of public space at the town-wide level and create an encapsulated town rather than a mixed, interactive community. Without the conspicuous walls of the Chinese condo their privacy depends on isolation, gentrification, and citizens’ decrees. Some of these are light-hearted enough — for example in Celebration it’s officially not permitted to be unhappy — but for China the success of 20,000 gated communities in the US presents a rather less frivolous scenario. As China progresses most likely similar desires for a neo-suburban lifestyle will burgeon. In the dichotomist Chinese environment, compounds sealed off from society threaten the durability of the suburb. The split cities* they produce prohibit the assimilation of migrants and low-income citizens into the suburban society.

ES: Okay, so tell me a little about the specific history of the actual designs themselves.

NM: Well, our first large urban commission in China was surprisingly progressive. We met a developer who from a commercial standpoint supported our ambitions for sustainability and urban diversity. The assignment was for an art and design district in Gao Bei Dian (GBD); an area of rapid change in east Beijing near the Fifth Ring Road. We felt this was a good example of the kind of space we aimed to capture with the Green Edge* concept. The area is a leftover plot wedged between highways, train tracks, and semi-urbanized villages*, but with impressive green features.

In the first stage the project was intended to be purely an art district with large art studios, loft apartments, and galleries and offices for the creative sector. As you know in Beijing recently dozens of areas have been designated for the creative industry*; sometimes this is an effective method to elevate suburban areas struggling with their industrial heritage. But often it’s merely a government label void of real meaning, and applied to postpone any clear decision. This put us on the spot to answer the question if an art district could really be designed — would this kill the grass-roots qualities? Should artists be left to find urban niches themselves, as they have done successfully across the globe? Art districts come and go and nowhere faster than in Beijing, and this is only normal. But in Beijing they develop under strangely contradictory forces. Some like Dashanzi 798 have been acknowledged and flourish; others have been painfully short-lived and leveled without notification. This constant threat made us decide that a well-planned creative district which would provide individual artists with a safe environment in which to live and work was worthwhile.

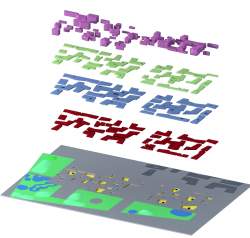

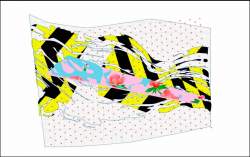

But as the project evolved so did the assignment and even the actual site conditions. The reality of our central hypothesis of dynamic density* became all too apparent. Our challenge for the two designs we had made was to develop systems that would be flexible, yet diverse and detailed. The level of detail expected in a Chinese urban proposal approaches the architectural scale, and this unfortunately eradicates most flexibility from the design process. I believe this is one of the reasons why in China instant designs are commonplace. Our efforts to achieve extreme flexibility allowed us to safeguard the search for creative solutions. The systems we’ve engineered can withstand continuous alterations while maintaining their principle qualities. The two systems presented here are based on organic principles: one a backbone, the other a cell pattern*.

ES: And how does this work out spatially?

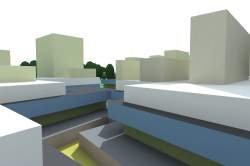

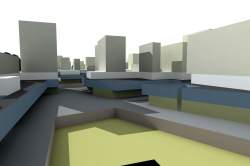

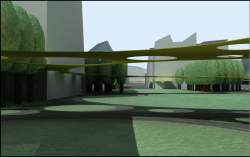

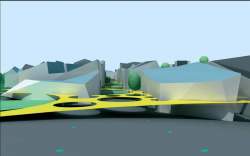

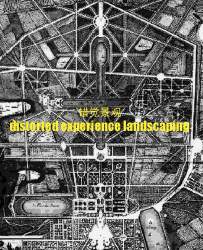

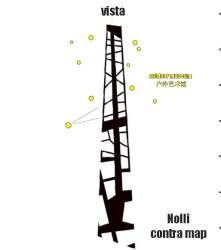

NM: The backbone or Strip* evolved from our desire to connect to the urban network via a public space at a time when the majority of real-estate projects turn away from the public domain. Providing a space that offers both circulatory and locational qualities can be the basis for a dynamic and diverse street life. The reality of the Beijing suburbs, however, literally left us looking for loose ends to connect. The project site is naturally as cut-off from its surroundings as any walled community. In response we have designed a single strip that is both origin and destination; a distinctly urban zone that forms the backbone for urban development in one direction, and a clear demarcation from the surrounding ecological park in the other. These two aspects of the project — city and park — work together as one ecological system that channels water flows and preserves energy. The ecological park replenishes the consumption of the urban strip. The park is a showcase for environmental design and encourages green consumers. The surface of the urban strip is almost entirely permeable and tapered to distort the perspective*. From each end the total distance looks either very long or very short. Visitors are naturally drawn deep inside the area and then persuaded to wander around through the park.

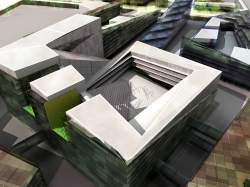

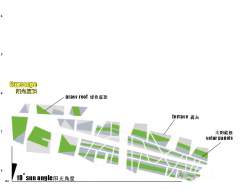

The buildings are wrapped along the central axis or vista and connected by a continuous tensile sun-screen that protects the pedestrians against the hot Beijing summer. The built volume slopes down to offer maximum penetration of sunlight and an enhanced view over the park. Sustainable projects are generally only open to the south, but art studios require northern light. This provided an interesting opportunity to develop an intricate roofscape. Jagged strips of industrial style light wells cut through the entire district. The windows face north, the south facing facades are covered with solar panels, the flat parts become terraces and walkways, the soft slopes are covered with vegetation. The natural qualities of the site have been enhanced with indigenous plants and natural installations such as the solar aquatic system* and reed beds.

Then the assignment grew, the site parameters shifted and the project gained a large amount of commercial and leisure program. The network of paths and designated routes we’d planned through the site became much more elaborate, while the available surface decreased. It’s an obvious solution to rely on tall structures to comply with Chinese building codes, and admittedly there are strong incentives behind the suburban skyscrapers we see emerging. But developed as single mega-compounds these environments more often resemble a form of Chinese Modernism* — large blocks on a map of endless undefined cross-hatched grass; an urban approach which is leaving neighborhoods oddly inaccessible behind vast empty spaces. Within the context of the Green Edge* we proposed to aim for a low-rise solution without compromising the density.

Using cantilevers, bridges, decks, skywalks and extensive sunken retail streets and squares the available space is greatly increased. Cars are removed from sight and the distinction between above and below ground, the street and the terraces is permeated. To achieve this, a formula was created for a single cell of 2,500m2 to be developed by a single architect. These cells are then grouped together to form larger patterns which can adapt to specific conditions such as trees or a river. The Chinese puzzle pattern of plazas and corridors is the result.

ES: Your proposals speak also about the social aspects of the design, suggesting even a resonance with ‘communist principles’, and offering a ‘soft transition’ from hutong* to skyscraper. How do you reconcile this with the market’s current fetishization of the new and apparent unconcern with demolishing previous environments? Communism in China has demonstrated a capacity to engage successfully in large-scale development projects, but this has not always produced an integrated approach to urban design.

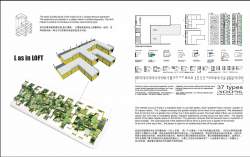

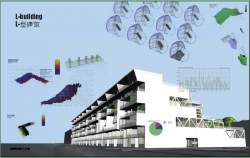

NM: If you look at things over a slightly longer term, there is absolutely no contradiction between marketability and social concerns for the user community. The L-building* is an architectural response to our research at the individual scale. Green projects, and particularly housing, need to be marketable. We feel that an increasingly critical consumer of living space will not accept the plastic-wrapped boxes on offer today much longer. A housing stock that offers greater diversity with preferably more comfortable homes is in itself more sustainable. This means part of the problem is purely architectural. I realize this is a direct critique of the design education in China that still has not been able to adopt a more conceptual approach, let alone nurture the creativity of its students, but sustainability, marketability, and attractiveness ultimately all combine to form a triple bottom line for any development.

The letter L in L-building embodies these qualities. L is the primary shape of the apartment, but L also stands for Luxury and for Loft. We have designed the units as lofts not merely as the epitome of the architect’s dream apartment, but as a space that can easily be adapted from one owner to the next. The apartments can be either completely compartmentalized or entirely open, and thus can be made suitable for couples, small families, or a new generation of single occupancy tenants born out of the one child policy.

The L-building as a whole introduces the further aspect of social sustainability, often missing in China and in the general discussion. Nothing is more desirable than an apartment with amenities such as running hot and cold water, a toilet, and a view. But for the inhabitant the transfer from the ping fang* — the simple derivative of the famous hutong* — to the modern tower block is often less rewarding as time goes by. The traditional Chinese neighborhood, including the danwei*, had an exceptional social coherence. Qualities of the ping fang* that were taken for granted, particularly the sense of community, are disappearing. Recreating a community for the individual within an environment of large-scale developments will become increasingly important in China, as more and more people find themselves not only relocated, but also questioning the benefits of that relocation.

Both the GBD Art and Design District and the L-building mediate between China’s traditional urban environment and the contemporary trend of up-scaling*; between low-rise and the modern tower block. First the L-building complies with some rudimentary suburban desires — a large private garden and your car at the door. But as a medium-sized, collectively developed, owned, and operated form, 1 the L-building also resonates with more traditional principles.

ES: Traditional principles as in the courtyard?

NM: Yes. It seems a contradiction and failed attempts prevail, but the Chinese courtyard or siheyuan* can be stacked. As a hybrid between a high-rise and a hutong*, the L-building retains the three essential qualities of a sizable garden, close connection to the neighborhood, and privacy. This is achieved by fusing the typology of the patio with terrace housing. The long walls of the immense terrace function as a courtyard on your rooftop. The protruding semi-cantilevered gardens catch the sun even when it sets behind the building. Walking to the end of your terrace you overlook the neighboring gardens, the park and the surroundings.

Note

1 The development model for the L-building draws on the capacity of the many dadui* in the suburbs to realize their own buildings on their own land.

A showcase of the future of Gao Bei Dian is on display at the Soldiers at The Gates exhibition Dashanzi’s 706 Space.

Neville Mars

Dynamic City Foundation

高碑店艺术设计区

来来去去的艺术区。遵循着应有的方式,没有比北京再快的了。有些只能痛苦的短暂维持,有些,如大山子798艺术区,渐显成果。仅在过去的几年里这里变化了,成熟了,有一些来自外界的威胁,商业化了并且成了大量大规模事件的举办地。它 在不断的进化。

随着艺术,升华的生活方式及设计成为城市发展雏形的最新动力, 问题也出现了:能否吸取798成功?艺术区能否被设计并且维持原有的基础特制?一个艺术区能否即高档,结合创意产业与商业用途,又为即将到来的艺术家们提供温床? 高碑店艺术设计区或简单的讲GBD是第一个尝试回答这些问题的地产。

我们在中国制定城市方案的前提是交叉城市网络;当大部分房产项目都被驱逐出公共领域时,要重新制定可以带来活跃多元的街边生活的公共领域。这就意味着要连接街道消除死路。然而北京近郊的现状留给我们的只是一些稀少的可以连接的死路。 这个项目基地毗邻高碑店五环路,与周围环境完全隔离。尽管离北京的中央商务区只有几分钟的路程,开发商也很渴望将这片地变成一个开放的可进入的艺术区, 但是被高速路环绕正如那些围墙社区,都与周围的环境相隔。

带路和生态园被现有的郊区紧密环绕,我们可以在自足的城市环境中寻找我们的自由。唯一的入口是进入这个坐落在全新生态园中丰富的生活和工作空间的通道。设计简化到一条道路使其既原始又是一个目的地;带路在一个方向引导无限定城市发展,同时另一个方向又清晰地与生态园分隔开。城市与园林两个不同的部分作为一个完整的生态系统工作, 引导水流节约能源。城市带路使商业区与艺术企业成为统一的邻里关系。生态园作为带路消费的补充。园林是中国环境设计和鼓励绿色消费者的展区。户外剧场在商业区的中心;户外美术馆艺术家村的焦点。

我们的目的集聚休闲,购物与居住最大可销售性。这就是说大量的拥护和观光者值得期待。为了减压,有效的转移人和车我们插入了一条巨大的带路作为开放的场地可以举行城市活动或在两边停车。这是一条主干,可以发展房屋,动态广场和可以举办大型公共活动的理想空间。带路形成了一个连续不断的有着不同城市功能区的区域。锥形的设计扭曲了透视。从两端的广场分别看去会有极长和极短的效果。观光者会自然的被吸引到艺术区的深处,带着好奇游览全区。所有的房屋都围绕中心轴建造或是说街景将周围的元素完美结合。房屋有一个完整的伸开的遮阳板连接,它可以保护游人免受北京炎热夏天之苦, 带领他们行走在房屋之间。轻金属和玻璃的房屋建筑提供了灵活的工作和居住空间,同时还具有工厂氛围。大量此类的工作室和公寓混合排列。天井和向街开放的外墙使得远处的房屋也可到达和有趣。巨大的水泥表面为艺术提供了私人的空白的画布。

生态园将城市带路完全包围在其中。 自然特制在当地植被中得到强化,并且在连接不同装置如太阳能水过滤系统,水草河床和风车下形成。 园林和带路的表面几乎全部是渗水层。屋顶向着阳光斜起,建筑的结构整个下倾,为日光和欣赏园林提供了最大的空间。

高碑店艺术区未来发展将展出在大山子798‘兵临城下’展览中。

Owned by neville mars / Added by Stephanie Yao / 17.8 years ago / 303432 hits / 9 hours view time

Backlinks

Tags

Latest Entries

-

secondlife city

-

GDB recolored

-

GBD screenshot

-

GBD Competition and new area Gao Bei Dian for Google Earth

-

GBD-green-wall -01

-

GBD-green-wall 7 images

Contribute

Login to post an entry to this node.